The Treaty of London in 1915 resulted in Italy being promised large parts of the Eastern Adriatic in return for switching, as the media described it then ‘one million bayonets’ to the Entente.‘ Britain and the allies believed that the unbreakable Western Front could be turned by an attack through Italy. Lloyd George himself felt that the best way to defeat Germany was to ,knock out the props‘. Rather like the Easterners, who a day earlier (25 April) were savoring Turkish delight on the shores of Gallipoli, the Entente thought that they could paralyze Germany by removing one of the southern, sloppier pillars of the Central Powers, the Danube monarchy.

The treaty assigned most of the Eastern Adriatic, the Julian March and South Tyrol to the Italians. In this presentation, I shall focus mostly on the Eastern Adriatic as it is this part that is linked most intimately with our area focus and the Balkan states of Serbia and Montenegro. Sidney Sonnino, the Italian foreign minister, claimed that:

‚Our aspirations in regard to Dalmatia are based on reason of military defence, in order to have a preponderant position in the Mediterranean.

This naval dimension would be highlighted by the Admiral of the Italian fleet Thaon di Revel, who claimed that:

‘Without possessing Dalmatia and the Curzolari, the Adriatic will never be a sea upon which Italy will feel herself safe.

The Curzolari islands are the group of islands consisting of Korcula, Lastovo and Mljet, strategic parts of the Adriatic that allow a dominant position on the Adriatic rather like Malta and Cyprus do for Britain in the Mediterranean.

In this paper, we shall see some of the aims of the treaty such as driving a wedge between the Triple alliance in order to prevent Germany from advancing south. It attempted to puncture the decades long fate of the Adriatic as a Central Powers lake. A year into the Great War, British public opinion was strongly influenced by pro-treaty British newspapers like the ‘The Spectator’ that claimed that:

‘To chase Germanism from the Adriatic is as essential as to drive it back across the Rhine’.

The findings include the correspondence of the Yugoslav committee with the Entente and various members of the British establishment leading up to and beyond 1915. I shall show how the London based Yugoslav committee lobbied against the Treaty of London by examining its correspondence with the various parties such as Supilo’s telegram to Sir Edward Grey. We shall see how and why some Britons like the Times foreign editor, Henry Wickham Steed, regional expert Robert Seton-Watson and the archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans lobbied actively against the Treaty.

I shall argue that they were inspired by a Romanticist view of 19th century Balkan nationalism as a new fusing force in European politics. This saw an Italo-Slavic alliance as a necessary force to contain German and Russian expansion but only in conjuncion with that other new bastion of liberalism, Italy. In the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, the South Slavs were seen as a force that will regenerate corrupt, materialistic and lost Europe. The regional expert and founder of SSEES RSW saw the Treaty as going against British interests of having an Italo-Slav alliance guard the South and the East against both Russians and Germans.

The Eastern Adriatic was the junction of Europe’s three largest people, Italian, German and Slav, all with historic claims to the region. Dante’s Inferno rhapsodized that Italy lay:

‘At Pula near the Kvarner, which encloses Italy and bathes her boundaries.’

The German community in Trieste was organised in the Schillerverein and saw Trieste as their ‘bridge to the Adriatic. In 1910, Trieste had a bigger Slovene population than Ljubljana. One of Slovenia’s greatest novelists Ivan Cankar famously stated that:

‘If Ljubljana was the heart of the Slovenes, Trieste was its lungs.’

Apart from the literati, the rationale for the Treaty of London included historic, strategic and ideological arguments. As I shall argue, certain sections of British public opinion, living in the twilight of Gladstonian/ Victorian liberalism saw Italy’s demands as a natural finale of the Risorgimento. For a large part of the 19th century, Slavic national emancipation against aristocratic, clerical and authoritarian Hapsburg rule was seen as possible only through the waves of the Italian Risorgimento. This included some of the numerous Adriatic multinationalists living in the Eastern Adriatic who Dominique Reill described in her book. One of them was the Sibenik born, Nikola Tomasseo. In 1848, as minister of education, il Dalmata was the right hand man of Danielle Manin, who led the 1848 Risorgimento revolution against the Austrians in Venice. He also wrote one of the most influential Italian dictionaries.

The anti-Austrian Croat Eugen Kvaternik would later ask Tomasseo to become the leader of a state independent from Austria. He published a book – La Croatie et la confedereation italienne‘ in 1859. As Italian unification gathered pace, a whole handful of Dalmatians such as the future Sentor of Italy Federico Doda participated in Garibaldi’s Sicilian expedition. For many on the Western Adriatic and some on its Eastern side, the treaty of London was merely the latest ripple of the emancipatory and revolutionary Risorgimento.

Supporters of the Risogimento on the Eastern Adriatic argued that it was the bulwark of Latinity, against, not in the Balkans. They argued that the presence of the Venetian empire on the coast had given numerous cities an ‘Italian’ physiognomy. Even The former building of the Austrian navy in Vienna, constructed in 1908, contains the coats of arms of the 16 major Adriatic ports, written in Italian even at the dawn of the 20th century. Up to 1909, despite being a minority, Italian was the language of administration, education and the courts. Therefore in 1915, dualist regions like Dalmatia had used Croatian as an official language for less than a decade.

Despite the Italian wars of unification, in 1915 some 800 000 Italians still lived in the territories from the Brenner Pass to the bay of Kotor. This poster shows Italy being baited by the different European powers by offers of different territories that were claimed by Italian irredentism. Tunisia in 1915 had more Italians living in it that Dalmatia. Italy’s entry to the war was seen as completing the Risorgimento. For pro-war Italians inside and outside the peninsula, the war itself became known as the 4th war of independence. The Treaty of London allowed Italy to complete the unity of the irredemed provinces show by this poster of the Italian king breaking the barriers and freeing the ireedemed provinces. These provinces are represented by three women of Dalmatia, Istria and Trieste.

Some 2000 Giulian, Istrian and Dalmatian volunteers participate in the 4th war of independence. Some 302 fell in combat. Scipio Slataper, Carlo Stuparich and Rugggero Timeus. Many left behind a significant literary opus that would shape the memory of the Eastern Adriatic relations between the South Slavs and the Italians well into the 20th century. Timeus, like many Italian irredentists living on the Eastern Adriatic borderlands, represented the more radical, anti-Slav and maximalist wing of Italian irredentism. Writing in his novel ‘Trieste ‘, published in 1914, he states that:

‘Italy must conquer Trieste not merely in terms of completing national unity but in expectation of imperial expansion towards the Balkan peninsula.’

The aims for Trieste was not merely symbolic. The port of Trieste was one of the busiest in Europe in the first decades of last century. It performed a similar function for Southern Europe what Hamburg performed to Northern Europe. If Hamburg was the door to the World, Trieste was the opening to the Mediterranean, the entry to the Levant and the route to the Far East. After 1869 it became known as the third door to the Suez canal. Lloyd Austria’s ships regularly sailed via Split, stopping at Suez on their way to Singapour. Therefore, the economic advantage of owning the Eastern Adriatic and its busiest ports at the top figured significantly in Italian aspirations.

Timeus’ writing carry an apocalyptic edge regarding the Slav-Italian national struggle:

‘In Istria the struggle is a fateful inevitability that can only be brought to conclusion by a complete disappearance of one of the two races that are fighting ’

These tensions between Italian and Slav, manifested firstly through a duel between Irredentism and Panslavism, carried on in some form or another beyond the First and Second World War. The second world war infused the ethnic nationalism element with an ideological element, as communist faced fascist, Christan faced secularist, West faced East in Trieste, the Berlin of the Adriatic, where according to Tony Judt, the Third World War threatened to break out in the aftermath of Tito’s occupation of the city. Local memory, based on commemorations and counter commemorations at various points is to this day strained. This is shown in the site of memory at Bassovica, San Sabba and the rest of the Karst up to this day.

Italy’s arguments were also strategic, claiming that control of the Eastern Adriatic allowed them to hold the keys of the Adriatic and be secure from all military attack behind two impregnable mountain walls on the northern Alps and the Dinaric Alps. By taking the port of Valona, in todays Albania, Italy hoped to shut off the Central powers supply lines by corking the Adriatic. The Trieste born journalist Attilo Tamaro would write a tract for the Royal Italian geographic society, The Treaty of London and Italy’s national aspirations, explaining the need for the treaty:

The terms of the Treaty are purely defensive. They propose, as a fundamental principle of Italian safety and European peace, the establishment of boundaries that shall restore the unity of Italy as a nation. p4

Tamaro does not spare the growing territorial aspirations of the South Slavs:

‚The southern Slavs in the Balkans…they would hold the key of all the Balkan economic territory and could shut it up at their pleasure, according to the vicissitudes of their politics, habitually impulsive, disorderly and imperialistic. Let us bear in mind that in 1915 Serbia had already acquired a torpedo boat. Is it possible to have hundreds and hundreds of kilometers of coast and yet to cherish no naval ambitions.

Tamaro, like Mussolini, was one of the numerous Italians who cut their teeth in both World Wars, tasting mutilated victory as an irredentist and mutilated territory as a fascist.

The media during the First World War testify to a strong Italian public relations offensive to communicate their message to the world. The strategic argument can be seen in detail by the Italian naval chief of staff, admiral Thaon di Revel explains the reasons for the Treaty of London to the US public in the New York Times:

‘Now Italy is a country which breathes and lives on the sea. Her two lungs are the Tyrrhenian Sea and the Adriatic. If you take away one lung from a man he will perhaps continue to exist, but all the same he will be asphyxiated and so, if you take the Adriatic away from Italy she will die of asphyxiation.’

De Revel adds a naval warfare dimension:

‘Our Dreadnoughts are shut up in Tarento because we do not possess a harbour large or deep enough on the Adriatic to hold a large squadron, whereas Austria exerts her Empire on the whole of the upper Adriatic… each channel, each isle, and especially the Curzolari, possesses excellent ports for a numerous and powerful fleet.’

Whereas the Italian coast from Otranto to Venice is entirely low-lying, without ports, without anchorages, exposed to the North wind, the Curzolari Isles and Dalmatia, I repeat, offer numerous and vast points of refuge, marvelous ports, and the possibility of navigating inside for shelter from the bad weather. No matter where an Austrian ship may be in the Adriatic, she can always find refuge by steaming a few miles and reaching the numerous channels of the interior; no matter where an Italian ship may be in the Adriatic she can only take shelter either at Venice or Brindisi, our only natural naval ports. But Brindisi and Venice are 1,300 kilometers apart, and, moreover, are not practicable for large modern warships.

The Curzolari constitute, so to speak, a bridge between Dalmatia and Italy, and this bridge is entirely in the hands of the enemy, who can make use of it just whenever he pleases. He can choose his own moment to attack, he can choose the place of attack and withdraw before being pursued, because Venice and Brindisi are too far off for us to come up in time.

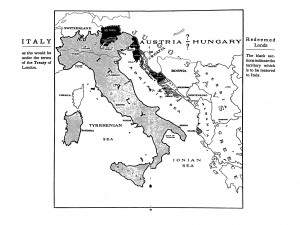

The map shows how Italys control of the Eastern Adriatic would help her shut the doors to invasion and suffocate the Central powers by corking the Adriatic. The admirals letter shows that Italy’s object is less nationality but rather strategic or in the words of the Italian foreign minister, ‘safety for future years’. This whole coast, he continued, was ‘the most vulnerable in the world’. Without a defensible port from Venice to Brindisi, the only way to guard against exchanging the incubus of Austria for that of Russia was to occupy as much of the opposite coastline as possible and fortify the islands. The Italian aim was to make the Adriatic her naval base. The admiral insists on the Curzolari group as the key to this sea, without which Italy could not hope to contain the expansion of Russian naval power after the war.

What were the justifications for the Treaty in Britain itself? Sir Edward Grey wrote to cabinet minister Buchanan that Italian intervention ‚will be the tipping point in the war‘. Buchanan wrote to Grey that : ‚We cannot strain the principle of nationality to the point of risking success in war.‘ Despite being part of the Whig party, it seems that during times of war, realpolitik trumped liberalist idealism. Britain’s affinity with the Appenine Peninsular went back to Venetian days. Shakespeare had marveled Venetian society in his plays. James I had written a pamphlet in defence of the most Serene republic, which shared much in common with England, a constitutional, maritime and mercantile empire fortified by nature. Napoleon, arch nemesis of Britain, had put an end to the Venetian empire and handed it over in the same year to the papist, conservative and reactionary Austrians. Venice in its pre-modern form and Italy in its modern form was an ideological reference point for parts of the liberal establishment and a potent cultural symbol that manifested itself into politics up to the treaty of London.

This affinity developed a new élan during Italian reunification that connected the previous affinity with Venice with a certain strand of British Whig politics that supported intervention in Europe. Like Byron, Trevelyan the elder had gone South to Italy in order to participate in the Risorgimento. Parts of the liberal party, following the anti-Austrian heritage of Gladstone, would have agreed with the Italian and pro-Italian population along the Eastern Adriatic in seening the Risorgimento an anti-clerical, liberal and progressive movement and thus the last libereto of the Risorgimento. French politicians who were raised in the spirit of l’ecole de la Republique would see no difference between Algeria being part of France and the Eastern Adriatic being part of Italy. British members of the Establishment, growing up in the spirit of the Union and having avidly followed the successful examples of German and Italian unification.

An extract from contemporary media tendentiously and deliberately refers to the Eastern Adriatic, as Italy’s other shore.‘ The article shows the major Roman remains in the Adriatic coastal towns of Split, Pula, Zadar and Kotor:

‚If you want a spectacle of beauty… you must slip out of the lagoons of Venice and steam across the Adriatic to what was once, and will be again, Italy’s other shore, Dalmatia. Some of it she only lost a hundred years ago , while in other portions the Lion of St Mark is still rampant, as in Zara.‘

Despite this, a significant opposition emerged headed by some prominent media and academic personalities. Seton-Watson’s Slavenfreundlichkeit emerges having traveled extensively around the Hapsburg Empire as a correspondent for the Spectator. Seton-Watson had published an influential book‚The Hapsburg Empire and the South Slav question‘. It is here that he makes his assertions that were to form the embryo of the future South Slav state. Three years before the war broke out, RSW wrote that Serbs and Croats belonged to one, Yugoslav race, would would eventually unite, just like the Germans and Italians had. Gradually, he started turning towards Serbia, whom he previously viewed with a measure of suspicion, even contempt. London thus became the embryo of important post-Hapsburg institutions that were to shape the Austro-Hungarian succession including SSEES, the New Europe lobby and the Yugoslav committee.As Larry Wolf claimed in June’s article of the Journal of Modern history, ‚Western representations of Eastern Europe;, Seton-Watson ‚worked with a Byronic paradigm as a sponsor of a national cause. Defining a south Slav question in his book a few years before the outbreak of the war, as Wolf claims, Seton-Watson:

‚Challenged the legitimacy of the Hapsburg monarchy just as the Eastern Question challenged that of the Ottoman empire.RSW inaugurated in peacetime a campaign that would escalate and intensify during the First World War.‘

In his book, die Sudslawische Frage, RSW had claimed that:

‘The whole Eastern Adriatic coast still remains an unsolved equation in the arithmetic of Europe and its solution depends upon the course of events among the South Slavs.’

In a letter to the Times a few days before the Treaty, Seton-Watson claimed that:

‘The South-Slavs main role is to bridge the abyss between East and West. They are our natural allies, as arbitors between Britain and Russia and between Britain and the great Slavic world’.

Seton-Watson examines the quality vs Quantity argument with a letter to the editor of the Nation newspaper explaining the Treaty of London to a British audience:

‚If the aims of the entente are crowned with success, at least 500 000 Slavs will be transferred from one alien rule to another. The feud will thus be still further envenomed and magnified it a quite needless conflict between Italy and Serbia, between the Latin and Slavonic worlds.‘

The founder of the School of Slavonic studies finishes with an appeal to the British public that calls for a New order in a new Europe:

‘The South Slav question is one which the British public opinion cannot afford to neglect. A close understanding between Italy and the South Slavs and Romania is an essential preliminary to any lasting settlement of the Balkan and Adriatic problems, and to the reconstruction of SE Europe on healthy national and economic lines; and if Dalmatia falls to Italy such an understanding will be ipso facto impossible.’

Spending a lot of his own money, Seton-Watson founded a voluminous weekly news paper, New Europe, which he used as a platform to air his anti-treaty views. The list of people involved and contributing included the editor of the Observer, the foreign editor of the Times, MPs and Bishops, therefore a broad range of people from the Establishment. RSW took a distinctly anti-treaty position. In New Europe, he describes it as ‚iniquitous‘:

‘Italy has as much right to Dalmatia as England to Bordeaux. By promising Dalmatia to Italy, we shall galvanize Austro-Hungary into new life. Germany has a better right to Belgium and Holland than Italy to Dalmatia’.

Writing in New Europe, the noted archaeologist and former British attache in Montenegro Arthur Evans drew a road map of Yugoslavia. Seton-Watson, Evans and HW Steed saw South Slav unity around Serbia as the only possibility for saving the Adriatic coast from going from one alien rule to another.

Why were these Britons so anti-treaty oriented? Seton-Watson wanted to set up a counter to Teutonic ascendancy in Europe, which was to become the London school of Slavonic Studies. Robert Seton-Watson followed a well-established, Romantic and liberal path trod by numerous British Europeanist. This started with Byron and Greece in the first part of the 19th century. It would carry on with Gladstone and Bulgaria in the second part of the century. The Yugoslavs were merely the latest pet Balkan nation embraced by a country of animal lovers who enjoyed adopting a pet nation.. This time, British ascendancy in the Balkans would occur through filling the vacuum left behind by the Austro-Hungarian empire with a series of smaller, Slavic yet anti-Russian nations. Solve the Eastern Question by Balkanising the Ottoman Empire.

Thus a Slavo-Italian liberal alliance that had seen the light of day in theory, this Adriatic brotherhood of nations would replace, papist, conservative and authoritarian Austria.Seton-Watson wanted to revitalise the 19th century concept of Adriatic multinationalism. Early Mazzini and Nikola Tommaseo considered Slavs as allies in the struggle for national and political emancipation. The private notes of RSW testify to a inherent admiration of the Adriatic multinationalists. In his notes, he makes a collection of the quotes of the major figures of Adriatic multinationalism, seeing in them the possibility of a future south Slav state and Italo-Slav friendship. On Tomasseo, perhaps the most famous crosses between the two sides of the Adriatic, Seton-Watson interprets his writings as setting the blueprint for an embryonic South Slav state:

‚In his famous ode to Dalmatia, he prophesies that she will one day be ‚reborn as Serbia. Dalmatia has remained more Slav than was Croatia, with all her pure Croats. While opposed to union with Croatia, he looked to union with Serbia as the true future for Dalmatia.‘

The Yugoslav commitee was to a certain extent a continuation of Italo-Slav co-operation. Many from it were disproportionately from Dalmatia. In 1915, from 17 members of the Comimittee, 11 were from the Eastern Adriatic. In 1918, out of 36, 24. These included including Supilo, Trumbić and Meštrović, all who had been educated in the Italian spirit. Supilo’s mother was Italian. All would have been aware of the Italian and German paradigm of unificaiton and they saw sense in a union with the Slav Piedmont. Together with their British supporters, they started an intense lobbying campaign against the Treaty on behalf of a post-Hapsburg, Slav led ascendancy in conjunction with the Italians. In a telegram to Professor Cvijic, Supilo outlines the views of someone who comes from the area that was to be given to the Italians:

‚A terrible injustice will be done to our cultured and civilized nation, if Italy is allowed to occupy our shores. Such a crime against our nation on the Adriatic could only be dictated by the brutal force of the stronger, in the same way as German militarism occupied Belgium. It is impossible to believe that Europe, which rose against Germany for this very reason, should now allow Italy to enforce the principle of the stronger against our compact and overwhelming majority on the Adriatic coast. By such a proceeding civilized Europe would only contradict all her own assurances to Belgium: for Italy does not enter to liberate but to conquer the territory and towns of our nation. We shall not rest until our brothers have been liberated and our coast is our own again. We shall be grateful to the Great British nation, whose interests nowhere clash with our but on the contrary are everywhere in harmony‘

The Yugoslav committee, based in London, issued newspapers regarding news from the Eastern Adriatic in English and French. The Parisian version of the Bulletin Yougoslave was edited by Hinko Hinkovic, who in his memoirs ‚Iz velikog doba‘, leaves revealing comments about the treaty of London:

‚An amputation of our coastal parts would cause such bleeding that our body would never be able to recover. On the European body, there will forever after lie an open, bleeding wound.‘ If Austria is our enemy, Italy is even a greater enemy.‘

In one of the issues of the Yugoslav commitee’s newspapers ‚Le bulletin yougoslave‘, there is a whole page dedicated to Mazzini and other Risorgimento members positive attitudes towards an Italo-Slav alliance, with the Slavs playing a partner role:

‚The Turkish and the Austrian empire are condemned to an inevitable daeth. The duty falls on Italy to hasten this death. The spear that will do this lies in the hands of the Slavs.‘

A contemporary Italian caricature plays upon this anti-imperialist element of Italy’s war entry, showing the KUK monarchy as a ravenous octopus..The Italian historian Cattaruza has argued that elements of the Italian establishment such as Gaetano Salvemini and Leonida Bissolati entered the war on a platform of national self-determination of all the people in the Hapsburg monarchy based on a fraternity between Italy and the Slavs. This re proposal of the early years of the Risorgimento uses Mazzinian ideas of politics that conciliates national sentiment with international solidarity.

It seems that the liberal members of the British establishment felt that Italy had deviated from the course of the noble Risorgimento emancipatory tradition, from Va pensiero to Aida. The treaty of London drives a wedge in the Italo-Slav, anti-Hapsburg alliance, which was criticized by media like the the New Statesman on 29 May 1915 stating that:

‘Italy’s Dalmatian policy is to be regretted for several reasons. It is a glaring departure from the principles of nationality, to which the allies have hithertoo paid hommage.‘

In a 25 page long memo called the Adriatic problem , Seton-Watson claims that the Italians have deviated from their noble independence project:

‘Baron Sonnino…his utter departure from the spirit of the Risorgimento’.p12

The Treaty of London destroys the liberal idea of the Risorgimento that joins both sides, blocking the prospect of a new Europe. Treaty of London a bait to force South Slavs of Eastern Adriatic to come into Serbia’s arms. But what was the reaction of Serbia? The country was more interested in Macdeonia and Bosnia, rather than the coast.The artist Mestrovic and member of the Yugoslav committee reports in his ‚Corfu declaration and the Croats on p421 that:

‚we felt gravely disappointed that the Serb members of the Commitee were not even slightly concerned aobut the treaty of London, by which Istria and Dalmatia would be sent to Italy.‘

What was the attitude of the Serbs? An interview with the Serb ambassador in Rome Mihajlo Ristic states that:

‚We Serbs will not create any questions because of issues related to 500 more ore less kilometers, or whether the Italian border will be in Trieste, in Zadar, in Split or Durazzo.‘

In his memoir, Mestrovic recalls a conversation with the Serb foreign minister Ljuba Jovanovic, which took place in Rome in 1915:

‚We want to get BiH and an exit to the sea, the rest does not concern us, we will have time later… BiH, Bosnia and Dubrovnik, the rest of the coast shall go to the Italians and Croatia shallremain with Hungary.‘

In the Bulletin Yugoslave, Pasic promises Italians predominant position in the Adriatic, Pasic gave an annoucement to Corriera della Sera correspondent in St Petersburg:

‚There are no serious misunderstandings between the Serbs and the Italians… we Serbs cannot deny the clear right of Italy to hegemony on the shores of the Adriatic…We also want the sea, but we are by no means seeking a war port, to close our fleet there. We merely want to get an economic outlet.‘.

Hinkovic remembers Pasic commenting during the Corfu declaration:

‚Ako vi Hrvati i Slovenic niste zadovoljni, slobodno vam je ne uci u drzavu, a mi cemo Srbiju zaokruziti nase Srpstvo i stvoriti za se drzavu koja ce ce obuhvatiti Srbiju sa Crnom Gorom, Vojvodinom, Srijemom, BiH te juznom Dalmacijom.‘

What was the reaction in the Hapsburg lands promised to the Italians? The Treaty acted as a lightning conductor for the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, as it acted as a motivator for South-Slavs to fight what was perceived as a perfidous invasion of their own territories. The Hapsburgs sent the South-Slav Svetozar Borojevic as a response to the Treaty of London. Borojevic’s appointment, the only South Slav who would become a field Marshall in the Hapsburg army. He was the major instrument for the counter-nationalist propaganda device as he represented a South Slav success story that was promoted by the media as a prolongation of the Radetsky and Jelacic type Austro-Slav loyalism. Numerous factors on the Isonzo front generated an atmosphere that united the Hapsburg army. Propaganda represented perfidious Italy as the hereditary enemy that had imprisoned the pope, amputated Lombardy and Venetia and was now threatening the strategic territories on the Eastern Adriatic. The lion of Isonzo would lead the Austrian army to 12 victories against the Italians between 1915-18. The Hapsburg deployment of the Austro-Slav Boroevic to the north-western military theatre provided ultimate legitimacy to the war in the eyes of the large South Slav population on the Eastern Adriatic borderlands.

In 1915, Boroevic was awarded an honorary doctorate from Zagreb’s Franz Joseph university. In a private conversation with the dean of the university, Franz Barac (a covert Yugoslav committee supporter), Boroevic is reported to have commented:

‘We are fighting here for our lands, for if the Italians took Istria, Dalmatia and Gorizia and deprived us of our most beautiful parts and with that our maritime traditions.’

As the war continued, the Hapsburg authorities responded to nationalist agitation by creating realms of Austro-Slav memory throughout the Eastern Adriatic and beyond. Boroevic became an honorary citizen of over seventy different towns and cities on the Italo-Slav borderlands such as Ljubljana, Varazdin and Karlovac.Cases of open Slovene or Croat subordination in the front line seems to have been small, especially on the Italian front where the Hapsburg officers could tell their troops that Italy had rapacious designs on the Slovene-Croat territory.

In the aftermath of the Italian defeat at Caporetto, the Yugoslav commitee met up with the Italians. This Congress of oppressed nationalitites brings together the Italians and the Yugoslav commitee, at least in theory achieving the Italo-Slav alliance that had been hoped for by Mazzini and members of the British liberal establishment.It represents the definitive adhesion of Italy to Mazzinian principles.

As the guns felt silent on the Isonzo front, a week before the peace treaty was signed in Compiegne, Italian troops marched into the lands of the Eastern Adriatic, far beyond what had been promised to them as we can see on the ethnic map of the Adriatic. The green lines represent the alleged Italian predominance in each major settlement of the Eastern Adriatic coast. The next slide shows pictures of the Italian tricoleur being hoisted in the town of Korcula, where some 410 Italian lived alongside a couple of thousand Slavs. The local Italians, taking the lions of St Mark as a permanent reminder of the legacy of the most serene republic, reported that the lion wagged its tail in delight as the troops of Victor Emanuelle marched in. The occupation of large parts of the Eastern Adriatic by Italy meant that the Italo-Slav question one of the biggest problems and non-resolvable issues of the peace conference in Versailles. The treaty of Rappalo in 1920 leaves some 400 000 Slovenes and 100 000 Croats remain in Italy. Italy got to keep Istria, Rijeka, Zadar, Lastovo and Palagruza.

What was the long term impact on memory? The Great War defines in the religions imagery of the fascists the myth of the resurrection of new Italy. In Italy, dissatisfaction with the post-war agreements gives birth to the legend of mutilated victory. D’Annuncio, the first Duce, who in defiance of Wilson would seize the port of Rijeka, calls Adriatic ‘Mare amarissimo’ and would claim in his famous work ‘la nave’, that ‘wolfs rule the sea’. Italy develops discourse of conquest through victimhood, which is embryonically developed at this period. This sets it off on a collision course with Yugoslavia for the next few decades. Borhut Klabjan has called this the Scramble for the Adriatic, indicating that there were elements of colonialism in this. Tensions relating to the Italian occupation of the Eastern Adriatic coast would lead to the first fascist act in Europe. Taking the shooting of the Italian captain Giulli in Split in 11 July 1920, extremists in Trieste incinerated the Slovenian Narodni Dom in Trieste, an act saluted by Mussolini as the ‘capolavoro del fascismo triestino’.

According to the US historian Rusinow, 1920 saw ‘the first Fascist violence struck Europe, with the police looking on as a mob burned down the Slovene cultural centre in Trieste’. The British historian AJP Taylor in his pamphlet ‘Trieste’ wrote ‘Italian rule over the South Slavs in the littoral had no parallel in Europe until the worst days of the Nazi dictatorship’. Yet opposition emerged soon.Europe’s first anti-fascist movement TIGR (Trst, Istria, Gorizia and Rijeka), contained the ideological embryo of the anti-fascist struggle which soon evolved beyond the borders. For the Slavs of the Eastern Adriatic coast, memories of the London treaty and the subsequent occupation mean that strong support for pan Slavism continued to exist. According to General Sarkotic, almost 100%. Punat on the Island of Krk renames itself Aleksandrovo as a tribute to the Karadjordzevic dynasty. The post-war organisation, Jadranska straza is one of the most numerous organisations in the whole of the SHS state and RSW would comment that despite their divisions:

‘Every Yugoslav would unite to defend Dalmatia against a foreign invader.‘

As the Italians left in the aftermath of the treaty of Rappalo, a dozen or so locals went on a vandalism round, making sure that the memory of Latinity, Venice and thus Italianess be removed. Vandalising lions would continue throughout the Eastern Adriatic during the interwar era, even causing a diplomatic crisis as the lions in Trogir caused Mussolini himself to make a comment. The image of the lion became ingrained in the local memory, representing the predatory side of Italian imperialism in all its formats, irredentism and Savoyism at the end of the First World War and Mussolini and Fascism during the second. Today on the island of Korcula, the date when the Italians left is marked by one of the main squares in the town. In a revealing local tribute to dualism, the square’s official name has never caught on, as locals still call it in the Latinized dialect, Plokata.