This paper was given at the Wiener Osteuropaforum Symposium on ‘Ethno-political conflicts between the Adriatic and the Aegean in the 1940s’ in July 2014

The slide shows the Italian ‘Pino Budicin’ battalion marching into Pula on VE day 8 May 1945. With its well-preserved Roman arena, the magnificent marble stones sang a fundamental truth for Irredentists, Italian nationalists and Grand Tourists. Pula’s Latin heritage symbolised the Italianess of Istria. Dante’s Inferno rhapsodised that Italy lay ‘at Pula near the Kvarner, which encloses Italy and bathes her boundaries.’ Nevertheless, an Italian Istrian from Rovinj, Budicin, signed the Pazin declaration that made Istria a part of Croatia. Budicin’s revolutionary act earned him a place in the Yugoslav pantheon of national hero. This revolutionary act created numerous revolutionaries within a previously reticent Italian community. A brotherhood of arms revolutionary discourse emerged. My paper will explore the melting (real or imagined) of ideological and ethnic differences. The avenue for combat created an opportunity for revolutionary inclined Italians to join in the ‘PL-revolutionary war’. By exploring the level of co-operation and confrontation between Italians and Slavs in the contested heart of the Adriatic, I shall shed light onto whether Italians like Budicin who shifted alliances were renegades or revolutionaries. Tearing themselves out of the straightjacket of national identity, Italian Istrians not only nail their colours to the mast. They sow a red star to their flag. As we can see on the image, the Italian speaking Budicin battalion achieves a symbiosis by trooping the Titini Tricoleur. As the language of the battalion was Italian, the Titini talijani sung the following song as an ode to Italo-Slav co-operation:

O Istria cara

Oppressa e insanguinata

Anche la vita

ti abbiamo noi donata

Avanti uniti

Croati ed Italiani

Nella certezza

Di un più bel domani.

Despite the image, the singing and the useful propaganda, more Italians would leave Istria in the 1940s than ever fought with the PLS. This did not stop the post-war instrumentalisation of ‘bravi italiani’. Italo-Slav co-operation was instrumentalised as the ultimate, supranational revolutionary act. These good Italians became part of the hegemonic socialist memory to forge a compelling revolutionary narrative. It demonstrated in the long term that Italians and Slavs need not be antithetically opposed in the future as they had been in the past. 1940s Italo-Slav co-operation in the long term leads to a borderland Istrian collective memory based on a post-national identity. Antifascism and multiculturalism as we shall see in the end remain the pillars of Istrianity. Italo-Slav co-operation contributes towards a grand principle of transcendence that refuses the ethno-political perceptions of history. Today geography trumps history through Istrianity, a strongly embedded regional identity rooted in the events of the 1940s.

Confrontation between Italian and Slavs in the Julian March has seen a lot of research. As a result of the permanent loss of most parts of the Julian March, historians like Pupo often focused on the questions of the ‘Esuli’, the exodus of thousands of Italians from the region. Between mutilated victory and mutilated territory, Istria sulphurically crystallises into a region of extremes.

Croatian historians like Dukovski and Slovene and Croatian historians like Repe have pointed out that Fascism’s first victims were Slavs. The 1920s Rappalo/Rome treaty had left millions of Slavs on the Italian side of the border. The writer, one time teacher in Istria and Peoples Liberation War fighter Nazor captures accurately the sentiment felt by many Slavs. The territorial adjustments were seen as an amputation, with a promise in religious terms to return:

Hold. Wait. Do not be tired by waiting, we shall return

For there is a covenant between you and us

Dear Istria, shorn from our parts

I bond thee, in moments like this, to all our hearts

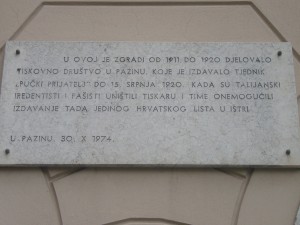

According to the US historian Rusinow, 1920 saw ‘the first Fascist violence struck Europe, with the police looking on as a mob burned down the Slovene cultural centre in Trieste’. Bora. The winds of the fascist bora spread like a summer wildfire. The day after the Narodni Dom arson, the seat of the Croatian language newspaper ‘Pučki Prijatelj’ was incinerated. AJP Taylor in his 1940s pamphlet ‘Trst or Triest’ wrote ‘Italian rule over the South Slavs in the littoral had no parallel in Europe until the worst days of the Nazi dictatorship’.

Opposition arrived soon. Europe’s first anti-fascist movement TIGR, representing the contested territories of Trieste, Istria, Gorizia and Rijeka contained the ideological embryo of the anti-fascist struggle. Internationalist opportunities were plenty in the interwar era. Italians and Slavs from Istria fought together in the Spanish Civil War. These Slav and Italian fighters are commemorated today in Koper, Slovenia with a bilingual monument containing Italian and Slav surnames. As we can see, Emilio and Giordano fought together with Ivan and Ante. Spain provided an organic foundation for an organised, co-operative and revolutionary struggle against 1940s Nazifascism.

In Istria, like most of the borderlands in our symposium, nationality overlapped with ideology. As the Second World War reached Istria, the Italy-Fascist/ Slav communist antithesis became starker. The Slav rebellion which began in April of that year quickly became a Communist-led Pan-Slav resistance to the ‘Nazifascist’ occupation. The older ethnic mental moorings became enmeshed and intensified with World War 2 political binaries.

The key event in Italo-Slav co-operation and confrontation is the Italian capitulation in 1943. Istria appears on the allied radar as a possible alternative route for the invasion of Europe. Churchill saw Istria as the doors through which the Allies could reach Vienna ahead of the USSR. The Germans were certainly not waiting for their northern neighbours. As Italian rule collapsed, the Wehrmach moved in. The Gauleiter of Carinthia, Rainer claimed that:

‘Istria and Trieste are for an Italian power only an appendage, but for Mitteleuropa they are a window to the Adriatic.’

A possible landing in Istria was constantly proposed by Churchill from the Tehran conference until the end of 1944. As Italian rule collapses, the first incidents of the foibe occurred. Ethno-political conflicts in the September days of 1943 represented for Italian victims the ultimate proof of the bestially brutal, Slavo-Communist, Balkan barbarians. The Slavs sought to clear the decks of any opposition before what they believed to be an imminent allied invasion through Istria. Italians who were seen to be representatives of fascism, the Italian state or purely political opponents were executed in the deep limestone pits in Istria. The hollow karst, the holokarst is the bloodiest episode of Italo-Slav confrontation and continues to haunt the memory of the area.

The end of Italian rule in Istra was used by the local insurgents to declare the unity of Istria to Croatia at a meeting in Pazin on the 13 September. Local Istrians Italians like Pino Budicin would also support the Pazin declaration. As district secretary of the KPH, Budicin was also a member of the popular commitee for the liberation of Istria and thus not under the command of the PCI. BUDICIN was the local representative to the ZAVHOH (state anti-fascist council for national liberation of Croatia) who he represented in Pazin. On the 20th Sept 1943, the ZAVNOH executive committee confirmed the decision of the Pazin committee. The ZAVNOH declaration guaranteed the Italians in Istria cultural autonomy. This would have a reason why Budicin signed the Pazin declaration but not the only one. Renegade? Or revolutionary? Responding to the dilemma between the particular and the general, Budicin and many other Italian revolutionaries chose communist, internationalist and triumphant Yugoslavia over imperialist, monarchist and reactionary Italy. The communist inspired resistance were influenced by ideology that claimed that they intended to rise above the nationalist hatred and petty imperialism. Budicin’s capture and execution, together with Slav partisans, as can be seen on this memorial plaque in Rovinj, gave Italo-Slav co-operation a revolutionary martyr.

Budicin was immortalised in the public consciousness by having a partisan battalion named after him that we saw on the opening slide. Integrated into the Slav Vladimir Gortan brigade, it represents the culmination of Italo-Slav co-operation. Significant efforts were made by the anti-fascist resistance to recruit the Italians of Istria to what was presented as a common struggle against fascism, imperialism and reactionary capitalism. Multi-lingual pamphlets witness the serious effort to persuade the Italians to join what they called the brotherhood of arms. The regional liberation committee on this slide, appeals in Istrian dialect to the distinct regional identity of Istrians:

Istrians,

the German-fascist beast is on its last legs

In the new Istrian battalions

there will be place for all honest sons of Istria,

Croatians and Italians.

March forward Istrians,

for your better and happier life.

The language used here refers distinctly to the Germans and the fascists, while excluding any ethnic reference to the Italians. These significant efforts were made to create co-operation between Italians and Slavs in Istria. The NLS appeals attempted to short-circuit ethno-political conflicts by establishing an alternative realm of identity to binary Italo-Slav identities, Istrianity. A few days after D-Day, the NLS seems to have wanted to show that there is room for non-Slavs revolutionaries in Yugoslavia even if they are not of Slav stock.

An Italian language pamphlet appeal to the ‘Youth of Istria’ to reject the renegades and join the national revolution:

Young antifascist Italians!

Put away all the plans of the renegade Italians who would again like to provoke contrasts between the Italian and the Croatian population of Istria. In the common struggle with the Croat youth for a new Istria within a democratic Croatia lies the guarantee of your liberty and of your better life.

Long live the brotherhood of arms between the Croatian youth of Istria and the youth of antifascist Italy

Written in Italian, it appeals explicitly to Italians of Istria to reject the reactionary remnants of the status quo. The description of nationally minded Italians as renegades demonstrates that the line between renegades and revolutionaries was often presented by the NLS as a binary choice. On the face of it, the communist parties of the two former enemies were rising above past discourse of ethnic based political conflicts through the brotherhood of arms.

Less than a week later, statements by the PCI formally cemented this Italo-Slav co-operation. When Hebrang, Kardelj, Dijlas and Togliatti met at Bari on Oct 19, 1944, Tolgatti affirmed that the PCI would favour the occupation of the Julian march by Tito’s army because:

‘There will be no English occupation, nor the restoration of a reactionary Italian administration’

Italo-Slavo co-operation was to continue diplomatically through union with a federal Yugoslavia. A return to Italy would be a return to capitalism under Anglo-Saxon, imperialist domination. Thus the possibility of shifting alliances allowed revolutionary Italians to be separated from their reactionary, reticent and renegade brethren. In the eyes of revolution inspired communist Italians, it was better to be a bulwark and advance post of the revolution against reaction than a bulwark of imperialism. Internationalism trumped both Italy and Yugoslavia. It represents a key rivet in Italo-Slav co-operation.

After VE day, the memory of Budicin became a tool to promote the foundational narrative of the antifascist struggle of Yugoslavia on the borderlands. Italo-Slav co-operation was constantly etched on public memory through organised parades of Italo-Slav co-operation as we can see in the article headline which notes:

‘Collective, common battle to destroy the fascist beast, which had brightened the face of the Italians in Istria and Rijeka’

Newspapers of the period convey a sense of honour being returned to the Italian community in Istria through redeeming themselves as revolutionary brothers in arms. As the legal and international status of Istria and other parts of the Julian March was still contested, the BudicinB intervenes in international diplomacy expressing affirmative sentiments in support of Tolgiatti’s idea of being internationalists ahead of Italians. According to this article, the fighters of the Budicin battalion demonstrate their shifting alliances with the words:

‘It is not Tito who wants Istria, but we (men of the Budicin battalion) who want Tito’

This caricature published in Glas Istre at the same time shows the internationalist rejection of Italy. The checkpoint is daubed ‘We want Tito’ in Italian, indicating to the reading public that the revolutionary Italian minority supported Tito, Yugoslavia and the new territorial gains wholeheartedly, comprehensively and unanimously. Glas Istre at that point carries a lot of articles that stress Italo-Slav co-operation reached into the public sphere to raise awareness and create more solidarity to those who are unsure about their position and fate within the new country. In nearby Vodnjan, the newspaper celebrated the bi-national internationalism forged in the heat of war:

‘Today the Italian reaction together with the global reaction would like to divide our people and create hate between the Italians and Croatians of Istria. These enemies of democracy will not succeed for the Croats and Italians of Istria are firmly united and fraternally joined up in the units of our national liberation struggle’.

This was not only restricted to the Croat parts of Istria. The following article explains how ‘Our democracy can only be built on Italo-Slovene brotherhood’:

‘The italo-slovene anti-fascist union believes that only on the basis of the people themselves, choosing their government, can we create an agreement for the guarantee of peaceful development in the spirit of italo-slovene brotherhood to achieve victory over fascism, to prevent the chauvinist provocations of imperialists and guarantee peace and security’

Brotherhood also meant sisterhood: Our languages are different, our hearts are the same.

‘The brotherhood of Italians and Croats is a brotherhood of common blood

Quantifying the number of Italians who co-operated with the Slavs in the anti-fascist struggle would perhaps give us the answer to the question whether they were renegades or reactionaries. According to Luciano Giurricin, Italian participation in Italo-Slav combat units was some 2000 in the summer of 1944. The triumphalist, heroic narrative put forward under Yugoslav rule put the Italians in a broader anti-fascist role in order to legitimise the rule of the new status quo post bellum.The likes of Budicin and people who fought in the NOB were presented as revolutionaries who were ready to live in a post-ethnic constellation. Glas Istre articles show us a consistent attempt of the state to present the Yugoslav Italians as heroic revolutionaries and their non-engaged, reserved and reticent co-nationals as the real renegades of humanity. Their history was inserted into the new narrative of the state, a patriotic legitimacy created by the antifascist struggle that had its roots in a continuous trajectory of socialist historiography.

As I have showed, there were indeed numerous individuals who could be described as revolutionaries as they went against the grain of ethno-political conflicts that had endured in one form or another since the early Risorgimento Period. As Balliger’s research has shown, many of the Italian revolutionaries were in fact disappointed. Franceso Sponza, who lead the Budicin battalion as they marched into Pula. He himself left Yugoslavia in 1952 as part of the exodus. His case shows that it was possible to be a revolutionary and a renegade and that the line is not as clear as is imagined.

The exodus is perhaps the starkest demonstration of Italo-Slav confrontation and shows the unravelling of Italo-Slav co-operation. In his introduction to the classic book on the Italian Exodus, Materada Milan Rakovac, the son of fallen Istrian national hero Joakim Rakovac and friend of Budicin, recognises the mistakes:

‘We, winners and revolutionaries, directly carried out with radical measures, uncritically and unselectively the unprecedented exodus from Istria.’

Despite problems with quantification, thousands of Italians left Istria. Gombac’s research has show that there were several reasons for exile, including voluntary, preventative and legal. After the Germans, Poles and the Ukranians, the Italians are the 4th largest group in terms of population movement in the 1940s. This monument to the Esuli in Trieste speaks of some 350 000 people who were force to leave not just Istria but the rest of the Eastern Adriatic. The esuli discourse of exile has become a constitutive experience of identity for Italian Istrians. Despite the quotations of Dante frequently featuring on Esuli banners, I would argue that the contemporary memory amongst the Esuli reflects less the medieval Dante but rather the Romanticist Verdi. The couplet from Nabucco best demonstrates the discourse of longing, etched in the exiles culture of memory:

Oh my homeland, beautiful and lost

Oh memory, so dear and fatal

The Esuli view the Italians that remained in Istria, the Rimanisti as the real renegades. Since 2005, when the Italian state declared the date of the Paris treaty a day of remembrance, Italy has been issuing commemorative Esuli stamps so that these victims of history are not forgotten.

What was the long-term impact on the diplomacy and the culture of memory? Positive memories of the 1940s period is reflected in the Istrian realms of memory. The revolutionary Italo-Slav brotherhood forged in the struggle against fascism has left its imprint in the public sphere as can be seen in the Istrian towns of Rovinj/ Koper in the forms of statues and bilingual street signs. The Italian flag flies near the Slovene/ Croatian flag from the town hall. In Koper, Tito still watches over the Italo-Slav co-operation in the town hall.

Italo-Slav co-operation in the long-term forged Istrianity. Having changed country 5 times in the 20th century, many residents of Istria have had difficulty in identifying with only one state or culture. Since the 90s, Istria has developed a strong regionalist identity as a way of dealing with toxic memory, destructive diplomacy and extremist politics. This new, non-nation oriented perspective of Istrian self-identification has thrived in the form of the IDS. One of the party’s intellectual founders Debeljuh writes of a ‘peculiar kind of authenticity, which is Slavic and Italian’. Promoting a hybrid, Latin-Slav identity, it has regularly won local majorities.

IDS conveys Istrians’ rejection of purist visions of any one state, culture or entity has thrived in the 21st century. The Istrian region became the first Croatian region to enter the council of Europe’s assembly of European regions. I am reliably informed that Istria gets by far the largest amount of project subsidies from the EU. Istria’s position in the last few decades allowed it to become a transnational region. It seems that the longer-term impact of the ethno-political conflicts in this borderland region has made it take advantage of its borderland status in the post-national constellation like South Tyrol or Alsace. When the IDS appointed its new chairman and current mayor of Pula, Boris Miletic in February this year, he paid tribute to the pillars of Italo-Slav co-operation; antifascism and multiculturalism, in his acceptance speech which you can see on the slide.

Istria continues to demonstrate its more liberal, multicultural values today. While the Pula arena accommodates outside influences such as ice hockey mactches and reggae concerts, the controversial Christian Rocker Thompson is refused permission to play. Last year, during the stormy bilingual signs debate in Eastern Slavonia, the pressure group ‘The committee for the defence of Croatian Vukovar’ was prevented from canvasing in Istria as their presence was said to threaten Istria’s multicultural model. It is not co-incidental that the first non-white person to hold political office in Eastern Europe was elected as mayor of the Istrian town of Piran. The Italian-Croatian writer Scotti’s description of the ‘always open Istrian heart’ today beats a louder than ever ‘da, ja, si’.