This paper was given at the symposium organised by the Institute for Danube and Central Europe in Vienna. The theme was ‘Remembrance culture and common histories in the Danube region’.

How do you successfully overcome the hallucinations of history in a region that successively experienced the twin totalitarianisms of fascism and communism? During the 1990s, the Istrian peninsula of Croatia politicized the vibrant, hybrid regional identity of Istrianity. It attempted to overcome the hallucinations of history by embracing geography as dissonant counterpoint to the suffocating, purist and overbearing nationalism of the ruling status quo. Having changed country 5 times in the 20th century, many residents of Istria have had difficulty in identifying with only one state or culture. In a region where many political entities have come and gone, according to the regionalists, only Istria has remained as a common, comfortable and universal identity for all. Politically, Istrianity crystallised in the 1990s due to heightened political paranoia of the decade, the fear of a collapsing economy and the overbearingly nationalist initiatives of the ruling Croatian democratic community. In the nervously turbulent 90s, Istrianity attempted to reimagine the peninsula into a demilitarised, European and multicultural realm that its supporters of the IDS (Istrian Democratic diet) felt could be transformed into the ‘Luxembourg of the Adriatic’.

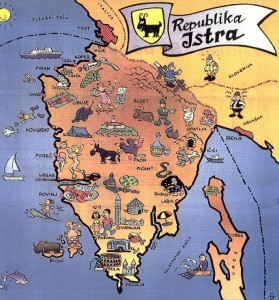

Istria lies at the hinge of the Adriatic, between Italy and the South Slav world, a hoofed-heart shaped peninsula. Regional identity suggested that Istrians, because of their multiculturality, proximity to Central Europe and hybridity were different from other Croats. The geographical space seems to indicate that the landlocked, livestock-heavy bulk of Central Europe is attempting to reach for a piece of coastline by jabbing a hoof into the Adriatic Sea. The hinge position that embraces the hybrid Italo-Slav identity, minus the Balkanic elements was what regional identity in Istria seemed to represent. Hybrids, living in hoof shaped peninsulas on a historically hinged environment.

Istrianity grew out of the remnants of the dualist borderland identity that had for centuries been nesting at the cultural crossroads. Istrianity found fertile ground within a peninsula that is simultaneously the buckle and heart of the Adriatic. A borderland history that hinges between three different worlds was embryonically institutionalised during the Habsburg Empire, effectively cultivated in the Second World War by the anti-fascist resistance and today has one of its leading members, Jakovic sitting in the European parliament.

My aim is to sketch the historical origins of Istrianity through its contemporary remembrance culture and common regional history. Using Pierre Nora’s concept of lieux de memoire, I shall demonstrate how monuments and public symbols from the Second World War Italo-Slav co-operation helped create Istrian regional. I have done research in local archives such as Pazin and Rijeka as well as traveled throughout the peninsula, trying to absorb the lieux de memoire in the form of naming public places such as streets, squares and monuments after symbols of Istrianity.

By the end of the 20th century, Istrians had the opportunity to experience and be dissatisfied with two distinct ideological regimes, communism and fascism. The mass population changes that included mass exodus, executions and border changes after the Second World War in particular would leave a trauma that only a multicultural, inclusive and post-national regional identity could heal. It has developed a strong regionalist remembrance culture as a way of dealing with toxic memory, destructive diplomacy and extremist politics. This new, non-nation oriented perspective of Istrian self-identification thrived during the 1990s, with regional identification regularly achieving double digit figures in censuses and emerged as a successful dissonant counterpoint to the HDZ.

The demographics, like the geography is mixed, with many parts being bilingual Italian and Croatian. One of the IDS intellectual founders Dino Debeljuh describes Istrianity as a ‘peculiar kind of authenticity, which is Slavic and Italian’. Despite achieving successful political representation in the 1990s through the IDS, the roots of Istrianty go back further back to the Habsburg era. Researchers like Ashcroft has interpreted Istrian regional identity as purely an economic endeavor, without taking into accounts other examples of multinationalist attempts in the region. I am interested to what extent Istrianity rooted in the Habsburg period, a continuation of the Adriatic multinationalist model that in the 19th century hoped to use the Adriatic as a bridge not just between the Slav/ Italian world but between East and West. Reill’s book ‘Nationalists who feared the nation’ examined individuals living in the Adriatic during the Hapsburg period who at a certain point felt that their different ethno-linguistic origins were not a barrier to an alternative Adriatic multinationalism. The Adriatic alternative, espoused by men who swam in Latin and Slav waters included Tomasseo, Valussi and Dal Ongaro. The movement claimed that national convergence points in Europe such as Tyrol, Corsica and the Ionian islands also included the Adriatic. Valussi claimed that these:

‘Borderlands of association between different nations are providentially placed by nature as rings between nations, as bridges of communication for affection, ideas and works.’

Multi-national space along the Adriatic thus signified connection, not separation, with Istria at its heart, buckling together East and West and Italian and South Slav. The sea did not act as a separator as it would in the first part of the 20th century. In fact, it joined together different peoples and their different languages, histories and customs. Matvejevic describes the Adriatic as the sea of intimacy, its many nations and cultures coming together in the buckle of the Adriatic, in Istria. This bordertopia promoted by the Adriatic alternative thought that nations needed to develop mutually rather than separately. Istrian regional identity, with its multicultural, inclusive and supranational tenets takes its inspiration from the Adriatic alternative with its roots theorized during Habsburg rule of the region.

Istria developed significantly during Habsburg Empire and the Danube Monarchy remains in the remembrance culture as symbolising construction, peace and prosperity. Istria, after centuries of being divided between the Hapsburg and the Venetian empire, becomes a constituted part of the Hapsburg Empire in the first part of the 19th century. It became a united territorial entity with its own diet. Economically, the region benefited from Habsburg rule. Investment in shipbuilding resulted in one of the more successful shipyards of the Adriatic, the still functioning Uljanik in Pula. Railways built from Trieste meant that Istria was connected to the large market in Central Europe and the first large wave of tourists began to arrive. Only through Istrianity were the two distinct imperial heritages of the Venetian and the Habsburg Empire brought together then and are brought together today.

Istrianity is partially contingent on what Magris has called the Hapsburg myth and the popularisation of Mitteleuropa as a concept in the 1970s. Indeed, Istrianity uses both tropes to officially transplant a micro-version of this sentiment to Istria. One notices the correlation indeed between the boom in tourism, which promoted Istrianity as a brand and the rise of the Hapsburg myth roughly at the same time in the 1970s. Memories of Austrian rule include that of an orderly country, with judicious bureaucrats, safe and fair tax burdens. Like Istriantiy, the Habsburg Empire was supranational. Istrianity identifies with the Habsburg myth i.e. representing social tolerance, administrative efficiency and institutional independence. The administrations that arrived after seem in the memory of Istrian to be backward, Balkan barbarians.

Between Italy’s mutilated victory in 1919 and mutilated territory in 1947, Istria sulphurically crystallises into a region of extremes. Coming under Italian rule after 1918, Istria suffered heavily under fascist Italy. The British historian AJP Taylor in his 1940s pamphlet ‘Trst or Triest’ wrote:

‘Italian rule over the South Slavs in the littoral had no parallel in Europe until the worst days of the Nazi dictatorship’.

World War 2 provided the fulcrum for the development of Istrian identity though a common history of resistance to fascism. The revolutionary forging of a brotherhood of arms between Italians and South Slavs in some cases based on an anti-fascist, Istrian struggle. Tearing themselves out of the straightjacket of national identity, Italian Istrians not only nail their colours to the mast. They sow a red star to their flag. Numerous Istrian Italians such as Pino Budicin, Aldo Rismondo and Marco Garbin nailed their Italian colours to the mast and joined the PLS partisans in order to fight against the common fascist oppressor. As we can see on the image, the Italian speaking Budicin battalion achieves a symbiosis by trooping the Titini Tricoleur. The Istrian Italian speaking batallion sung the following song as an ode to cross national co-operation and Istrian identity:

O Istria cara

Oppressa e insanguinata

Anche la vita

ti abbiamo noi donata

Avanti uniti

Croati ed Italiani

Nella certezza

Di un più bel domani.

The end of Italian rule in Istra was used to declare the unity of Istria to Croatia at a meeting in Pazin on the 13 September 1943. Interestingly, Istrians Italians like Pino Budicin would also sign the Pazin declaration that assigned Istria to Croatia, seeing the interests of Istria trumping those of Italy. Budicin’s revolutionary act earned him a place in the Yugoslav pantheon of national heroes. Today in Pazin’s main square of Istarskih velikana (Istrian greats), we can see his statue among that of other Istrian icons such as reverend Juraj Dobrila and the bard of the PLS Vladimir Nazor. The square shows the variety of individuals associated with Istriantity. Although diverse in their political, religious, ethnic and social origins, what unites all of them is that they are remembered as Istrian greats within a post-national Istrian identity.

Budicin was immortalised in the public consciousness by having a partisan battalion named after him that we saw on the previous slide. Significant efforts were made by the anti-fascist resistance to recruit the Italians of Istria to what was presented as a revolutionary common struggle against fascism, imperialism and reactionary capitalism. Multi-lingual pamphlets witness the serious effort to persuade the Italians to join what they called the brotherhood of arms.

The regional liberation committee on this slide, appeals in regional to Istria’s diverse population:

Istrians,

the German-fascist beast is on its last legs

In the new Istrian battalions

there will be place for all honest sons of Istria,

Croatians and Italians.

March forward Istrians,

for your better and happier life.

The language used here shows significant efforts to create co-operation between Italians and Slavs based on a common platform of regional identification. The NLS appeals attempted to short-circuit ethno-political conflicts by establishing an alternative realm of identity to binary Italo-Slav identities, Istrianity. Monuments to the PLS in Istria, such as this one in Pazin, explicitly refer to the regional, rather than national identity that helped forge a common history and a shared remembrance culture among all Istrians.

Glas Istre, the major newspaper of the peninsula supported Italo-Slav co-operation as you can see in the newspapers here. These good Italians became part of the hegemonic socialist memory to forge a compelling revolutionary narrative, a common history and a unifying remembrance culture. Istrianity can be traced to this attempt to demonstrate in the long term that Italians and Slavs need not be antithetically opposed in the future as they had been in the past. Italo-Slav co-operation contributes towards a grand principle of transcendence that refuses the ethno-political perceptions of identity and embraces a common history through a post-national, regional remembrance culture. When the IDS appointed its new chairman and current mayor of Pula, Boris Miletic in February this year, he paid tribute to the pillars of Italo-Slav co-operation; antifascism and multiculturalism, in his acceptance speech. On its sign, the IDS has three goats, representing the three major communities of Istria, Croatian, Italian and Slovene.

Positive memories of the 1940s period is reflected in the Istrian realms of memory. The revolutionary Italo-Slav brotherhood forged in the struggle against fascism has left its imprint in the public sphere as can be seen in the Istrian towns of Rovinj in the forms of statues and bilingual street signs.

This strong regional sentiment carved out over the decades received an economic element during the mass tourism boom in the 1970s. In the aftermath of the Treaty of Osimo in the 1970s, which regulated the border, the return of tourism in Istria created large-scale prosperity. This tourism boom of the post-war era acted as a stimulant to Istrian assertions of singularity. The Istrian brand itself became marketed as something hybrid, a marvelous mixture of Mitteleuropean melancholy and Mediterranean flair and thus exotic to the droves of Western tourists that came to visit the sunnier side of socialism. Post-war regional identity grew as a result of post-war prosperity with the so-called Alpe-Adria region. Geopolitical storms in the 1990s for many Istrians threatened the peace and prosperity that their borderland status had created.

How did Istrianity fare in the political arena? The IDS stood as a multicultural counter-narrative to the unitary nationalism prevalent in Croatia during the 1990s. It offered a new, co-operative form of remembrance based on the region’s traditional borderland dualism. Winning local majorities in the elections of 93, 95, 97, 99 and 2001, the IDS reflected Istrians’ rejection of purist visions- explicitly those of the HDZ, whose intense nationalist agenda came across as corrosive to the Istrian inclusive, tolerant and multicultural model. The government attempted to shut down Novi List and Glas Istre, two independent news sources in 1996. The HDZ extended its influence on the political scene and labelled every form of opposition a dangerous act. The support of some sections of the HDZ for the Croatian involvement in the war in Bosnia damaged the reputation of Istria abroad and sabotaged the revival of its tourism. IDS’ anti-militaristic stance meant that it was accused of treachery. In an interview with Ashbrook, the key figures of Istriantiy Emilio Soldacic and Jakovcic claimed that the HDZ used the same fascist methodology as Vladimir Meciar of Slovakia before the Slovak elections in 1998. They also accused the HDZ of ruling in the manner of a mob syndicate.

On the issue of bilingualism, the IDS platform seemed to go against the HDZ’s attempts of rigid centralisation and homogenisation. It attempted to undermine multiethnicity, a primary characteristic of Istrianity. The statute of the region, Articles 8 and 11 of statue, stating ‘multilingualim’ of Istria and ‘recognising the value of Istrianess’ was struck down by the Constitutional court of Croatia. The first was seen as particularly oppressive, as several key members of the IDS were either wholly or partially Italian. Dino Debeljuh compared the attempts of Mussolini and the fascist to erase Croatian identity in the inter-war period to the push by the HDZ to promote it in the 1990s. This state sponsored, suffocating nationalist discourse eventually strengthened the regional differentiation and HDZ would only ever get 1 MP from the whole peninsula.

What about the criticism of Istrianity from outside Croatia? Ballinger have argued that despite its modern, inclusive rhetoric, Istrianity also contains the old central European/ Balkan trope of cognitively othering a poorer, less developed and more Eastern neighbor. Her work criticised the cognitive boundaries of IDS that are alike to orientalism:

‘In my own research Istria over the past decade, I found that such Orientalism informed the explicitly progressivist program of the Istrian regionalist movement. While rejecting the nationalism of Tudman and promoting a regional identity, the IDS and its supporters nonetheless stresses Istria’s European credentials in a manner that depicts all non-Istrian Croats as less European and more Balkan. This regionalism ultimately works at both the conceptual and everyday levels to exclude newcomers to the peninsula, in a manner not so different from the exclusive ethno-nationalism it explicitly opposes. ’

A year after the death of Tudzman, the IDS joined the coalition government in 2001, with its chairman Jakovcic duly receiving the portfolio as minister of European integration. By this time, the wind had been taken out the IDS’ sails. With the revival of tourism and a firm commitment to EU entry, the appeal of the IDS regional party program declined as the economic benefits of being a borderland region started re-emerging. Istrian politicians realised that they could expect more from the European capital rather than their own by taking the regional route rather than the national route. The Istrian region became the first Croatian region to enter the council of Europe’s assembly of European regions. Today Istria gets by far the largest amount of project subsidies from the EU. While the rest of Croatia have received subsidies and funding for 18 projects from the EU, Istria has galloped ahead with 92, dwarfing the rest of the country.

As the economy picked up and the turbulent nature of the 90s became a memory, Istrianity as a political project declined as much of its proposals were integrated into the regional constitution. Today the Istrian regional constitution describes the region as a: ‘Multiethnic, multicultural and multilingual community.’ Article 6 confirms the parity of Italian with Croatian at all levels of administration and education. Article 10 explicitly supports transborder co-operation with Slovenia and Italy. Article 20 talks about the ‘cultivation of Istrianity as a traditional expression of regional Istrian multiethnicity’. An act in 2002 enshrined the use of the Istrian hymn ‘Krasna Zemljo’ as the official hymn of the region, written exactly a hundred years ago by an Istrian student in Vienna.

Istria continues to demonstrate its more liberal, multicultural values today. While the Pula arena accommodates outside influences such as ice hockey matches and reggae concerts, the controversial Christian Rocker Thompson is refused permission to play. Last year, during the stormy bilingual signs debate in Eastern Slavonia, the pressure group ‘The committee for the defence of Croatian Vukovar’ was prevented from canvasing in Istria as their presence was said to threaten Istria’s multicultural model. The Italian-Croatian writer Scotti’s description of the ‘always open Istrian heart’ today beats a louder than ever ‘da, ja, si’. In the Istrian spirit, I would like to finish with a hvala, danke, grazie and thank you.