This presentation was given at the symposium in Graz ‘Nationalism in times of uncertainty’ at the panel ‘Nationalism after Empire- Contesting territory and identity after World War One’.

The ‘scramble for the Adriatic’ surfaced tempestuously on the international arena with the 1915 Treaty of London.

´there is no reason why we should not acquiesce in the Adriatic becoming strategically an Italian lake. The advantages of preventing Austria from having a navy are overwhelming. One hostile great power will be eliminated from the Mediterranean

The Adriatic, due to its feeder route position for the Central Powers navy, became an important in the First World War. The Adriatic Question became a strained transnational question during and beyond the First World War. It reached global prominence at Versailles, where The American Journal of Law described it ´one of the most seriously vexing questions with which the peace conference was confronted and left unsolved´. It would be on the Adriatic that Wilson´s principles of the 14 points would be used to break the ´iniquitous imperialism´ of Italian irredentism´s ´fourth war of independence.

I have used the archives that have dealt with the Adriatic Question. I have two proposals:

Dalmatia- previously seen as a connector between the Eastern (Slav) and Western (Latin) Adriatic by 19th century partisans of the Adriatic alternative, as a result of the Italian occupation, becomes a connector between the Serbs and the Croats.

Crystallisation of South Slav identity in times of uncertainty such as foreign occupations- In times of uncertainty, such as occupation, the disparate South Slavs fuse together for the greater good. This results in the Adriatic Question being the question which divided the South Slavs the least.

THE ADRIATIC STAKES DURING THE WAR

Italy, who had remained neutral in the summer of 1914, soon began to see the possibilities of territorial expansion as a result of the First World War. In negotiations with the British in the treaty of London, the Italian ambassador to the UK Imperialli had pointed out to foreign secretary Sir Edward Grey that Dalmatia: ´for six centuries had belonged to Venice, and till 1866, was Italian by nationality. If since that date the Italian element had been weakened, it was owing to the deliberate policy of Austria in introducing a Slav element.

In the 1866 war, Italy had been able to gain Veneto and the surrounding area. Nevertheless, the Italian navy was defeated in its attempt to occupy Dalmatia at the naval battle of Vis. This defeat was seen as an aberration by the Italian military and an amputation by Italian irredentists, since Veneto and its surrounding became cut off from its Dalmatian territories for the first time in centuries. Il cancione del Adriatico lyrically captures a wartime battle cry calling for revenge:

I morti di Lissa The dead of Lissa

sono tutti risorti: Have all arisen

dai nostri porti From our ports

salpan le navi Sailing our ships

dov’eran gli schiavi Where the slaves

saranno i redenti Will be freed

Since then, Italian influence in the Eastern Adriatic parts of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy would decrease. As the 19th century wore on, the number of Italian controlled municipalities in Dalmatia went from 84 in 1861 to 1 in 1914. In 1909, Italian was replaced by Croatian as an official language in Dalmatia, leading many Italians on both sides of the Adriatic to fear for their existence.

Although Split had been left out of the territories given to Italy by the treaty of London, the sentiment of Italianità, a cultural-political identity that embraced both Slav and Latin (and according to some included its own language-Slavo Dalmatian) existed. The notion of jus primis ocupantis went back to antiquity. Dalmatia had been part of Roman Empire, with several emperors being born there including Diocletian, whose palace at Split even in 1914 seemed to stand as an architecturally enduring imprint of the Italian civilità. The ´citta di Diocletiano´, like many Dalmatian larger towns contained a sizeable Italophone population that included both ethnic South Slavs and Italians. The Split born former student of Vienna university in his 1915 pamphlet ´Italia e Dalmatia´ points out the cultural justifications for ´liberating´ the irredemed lands on the Eastern Adriatic:

Dalmazia- dopo il Lazio, dopo la Toscana e dopo il Veneto- la provincia d´Italia più ricca di opere d´arte nostra1.´ Spalato, dopo Roma e dopo Pompei, è forse la città piu ricca di monumenti romani´.

This message was broadcast beyond the shores of the Adriatic. In the UK, pro-Italian newspapers featured the city as belonging to ´Italy´s other shore´. The Lord Mayor of London even supported a media campaign of ´Italian flag day´.

The position of Dalmatia linguistically and ethnically was ambiguous one hundred years ago. The last Austrian census in 1910 reveals a clear majority of South Slavs in Dalmatia and a more balanced picture slightly in favour of the South Slavs in the Austrian littoral. However, Italian nationalist leaders in Dalmatia disagreed with official statistics and saw them as manipulated. The leader of the Italian community in Zadar, (the largest in Dalmatia) Robert Ghlighanovich, claimed that Dalmatia´s population of 600 000 contained 100 000 Italians, using the qualification of Italian ´by origin, by language and by custom´. Other included the ´100 000 Orthodox Slavs and 400 000 Slav peasants, a vast rural class, with no culture´ and according to Ghliganovich´ not in possession of a national consciousness´. The Zadar politician explains in his works that ´the Slav farmer knew he was not Italian but felt nothing apart from being a Dalmatian peasant.´ He argued that for opportunistic reasons related to cronyism, nepotism and other forms of expediency numerous Italians declared themselves Croats in census´.

Italian pamphlets on the Adriatic Question argued that the: ´national question cannot be reduced to a purely numerical value. The English are not disposed to renounce Egypt in favour of the Arabs or South Africa to the Boers. While the French are not going to renounce the reconquest of Alsace-Lorraine since Germans there form a majority of the population. An implementation of the nationality principle would also have as a consequence the dismantlement of Belgium to the advantage of France and Holland.´

DALMATIA AS THE SOUTH SLAV CRADLE

Despite its Roman and Venetian heritage, Dalmatia was also one of the cradles of the Croatian rebirth and South Slav nationalism. Through its writers, artists and sculptors, Dalmatia had participated in the Renaissance. Marko Marulic´s work Judita is recognised as the first epic in the Croatian language, dating back to 1501. Dalmatia´s intellectual co-operation with other South Slavs goes back to the 19th century when Niccolo Tomasseo hopes in his poem Alla Dalmazia that Serbia will invigorating Dalmatia and the South Slav world:

Ne più tra l´monte e il mar,

povero di terra e poche ignide isole sparte

O patria mia, sarai, ma,

la rinata Serbia-

guerriera ma no e mite site spirit

According to AJP Taylor, this was the only province in the Austro-Hungarian empire where there was ´genuine co-operation between Serbs and Croats´. One of its most ardent partisans of this co-operation in the early 20th century was the Dalmatian politician Josip Smodlaka, who had personally met Garibaldi in 1904 and announced the anti-Austrian nature of the Croats in Dalmatia to the figurehead of Italian unity as well as the Serbian king on a visit to Belgrade. Smodlaka and the leaders of the narodnjaci movement would form the core of the unitarist, pro-South Slav unity exile group in London, the Yugoslav Committee. Anti-Austrian, Pan-Slav and unitarist, its principal members hailed frequently from Dalmatia including Frano Supilo, Ante Trumbić and the sculptor Ivan Meštrović. All would have been aware of the Italian and German paradigm of unification and they saw themselves as the 20century executors of Tomasseo´s dream.

1918 ON THE ADRIATIC

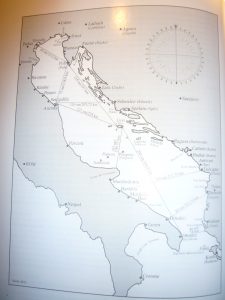

As the Habsburg empire sunk into the storm of history a week before November 11, 1918, Italy occupied large parts of the Austro-Hungarian seaboard. Italian maximalists saw victory in their latest war of independence as rightful justification for territorial acquisition, as you can see on this ethnic map which argues that large parts of the Eastern Adriatic coast promised by the treaty of London like Rijeka, Split and Korčula were exclusively ethnically Italian. The fear of invasion led to local leaders to seek salvation in the unity of a South Slav state. News of the declaration of the SHS state was greeted with glee by some of the population. The one-time student at Graz University, Gajo Bulat wrote in the newspaper Novo Doba the following:

´U ovom velikom historiskom času kada je vaše kraljevsko visočanstvo prvim svečanim državnim činom sankcijoniralo sve težnje našeg troimenog naroda i nas za uvijek neradružljivo ujedinjila…s ovih krasnih obala I otoka, s našeg mora što ga nikakva sila više oteti neče, ide Beogradu samo jedan oduševljeni poklik I neka živi naša osloboteljica junačka Srbija! Neka živi otac domovine njegovo veličanstvo Kralj Petar! Neka živi zenijalni zazdatelj Jugoslavije kralsko visočanstvo prestonasljednik Aleksandar. ´

Yet Bulat did not speak for all in Split. On the same day as Novo Doba published its article, posters went up around Split that pleaded expressing concern about the fate of the Italian population who feared for their fate in a South Slavs state. The two posters around the time when the South Slav state was proclaimed, show an insecurity about the position of the Italians of Split and an appeal for intervention and protection:

´From the city that has suffered the most for the defence of its Italianita…we Italian students invoke…the protection of Italy! The city that has for 50 years atrociously suffered from the pitiless persecutions from the violence of Austrian bayonets that in 1882 was shamefully abandoned to the mercy of the Slavs. We want to return to the king and the Italian people and be free from the overbearing threat of the Croats that are more tyrannical than the Austrians.´

The idea of savage Slavic highlanders that have only arrived recently and were barbarically oppressing the peace loving Italian lowlanders was communicated systematically by Italian politicians, the military and intellectuals to the world audience. A letter written to Seton-Watson by the Italian politician/ university professor Antonio de Vitti de Marco pointed out that: ´Italy can´t abandon the Italian groups living there in the hands of savages´. Writing to the US president on the eve of the Versailles conference, Italians lobbied and campaigned for the annexation of Dalmatia by attempting to persuade Wilson of the Italianess of the Dalmatian coast using an othering argument of barbarism vs civilisation:

´Dalmatia belongs to Western civilisation, to the civilisation of Italy. Every building and monument in Zara, in Sebenico, in Trau, in Spalato, in Ragusa, in Cattaro, is the product of Italian art and Italian culture. The Croats are new comers in Dalmatia…Croat influence in Dalmatia has been brought to bear amongst the ignorant Morlachs chiefly through Croat priests and monks, fanatically adverse to the Italian name and the Italian enlightenment. Only by violence and by fraud…have the Croats become masters of some of the Dalmatian cities, especially of Spalato. Neither Italy nor Western Europe can afford to expose to the encroachments of Balkan violence the coasts of the Adriatic.

The Italians, having signed the treaty of London certainly expected that they would get that as a minimum, despite the fact that statistically the number of Italians in Dalmatia was minuscule. Nevertheless, the historic argument of quality (if not quantity) led to the leader of the Italian community in Split, Ercolano Salvi to point out the irrelevance of the geographic and ethnographic element:

It is not numbers that count but culture and civilisation. Like Sardinia and Corsica in the Tyrrhenian sea, Dalmatia is an Italian island in the Adriatic.

As the Italians would frequently point out, Sardinia is further away from the Italian coast than Dalmatia. It is important to point out that the territory contested in Dalmatia between the SHS state and Italy, both Italians and South Slavs invoked a far-away force, one across the sea (Rome), the other across the mountains (Belgrade). In fact, Split is only marginally (355 km) closer to Belgrade and 368 away from Rome. However, Split is closer to the Italian coast than it is either to Belgrade or Zagreb.

The Italian nationalists raised the stakes. They started a campaign all over the country with the slogan ´the entire Dalmatia and Fiume´ basing their argument on the power principle, social Darwinist ideas and the notion of the war between races. Here we can see Alessandro Dudan´s poster of a lecture that purports to prove the 20 centuries of Italian civilisation in Dalmatia. On 15 January 1919, Gabrielle D´Annunzio would write his famous ´letter to the Dalmatians´, appealing to the province collectively but dedicating his letter to Ercolano Salvi, the leader of the Italian community in Split.

THE PEACE TREATY NEGOTIATIONS

As the Versailles negotiations began in early 1919, the Italian delegation would include numerous Italians from the Eastern Adraitic such as Alessandro Dudan mentioned earlier. It would be another, the Trieste Italian Salvatore Barziani who in a memorandum pressed Italian claims to both Rijeka and Split, which had not been promised under the Treaty of London. The Italian delegation circulated these bar charts that proved the alleged 20 centuries of Italian domination in Dalmatia, including in their count the Roman empire and the Venetian empire. The Italian minister of foreign affairs Sidney Sonnino told the British Prime Minister Lloyd George that the ´Dalmatian coast was the boulevard of Italy through the ages´.

Yet the Italian delegation´s attempt to gain both Dalmatia and Fiume was contrary to President Wilson´s idealist internationalism that had been outlined in the 14 points. The 9th point being particularly relevant as it stated that Italy´s frontier should be adjusted ´along lines of nationality. The division between Italians and Slavs represented to Wilson the fundamental chasm between Western and Eastern Europe. For Wilson, the treaty of London became a symbol of the deplorable old world in need for reform. Italy was soon shunted aside as the black sheep at the Versailles conference.

With 600 000 Italians dead and 500 000 disabled, Italy´s politicians felt they certainly deserved the minimum that they were promised and were horrified by the idea that conditions had changed since 1915. Sonnino considered the treaty of London as one of his great diplomatic success and an agreement that finally won Italy a place among the leading powers of the time. Sonnino responded with a stubborn attachment to the Treaty of London, which he considered the sole certainty in such a dangerous and confusing international setting. According to him ´To discuss war aims implies revision, revision implies renunciation. ´Yet the American president Wilson scorned the old-world diplomacy based on secret treaties, realpolitik and imperialism and saw the chance to make an example of Italy. Wilson´s assistants wrote in April 1919 that:

´Never in his career did the president have presented to him the opportunity to strike a death blow to the discredited methods of old world diplomacy…to the President is given the rare privilege of going down in history as the statesman who destroyed, by a clean cut decision against an infamous arrangement, the last vestige of the old order.´

With Bolshevik copycat revolutions breaking out in Hungary and Bavaria, Wilson also feared that the South Slavs could also potentially fall to Bolshevik inspired insurrection. Wilson´s refusal of Italian maximalist demands and a direct appeal to the Italian population led to the Italian delegation leaving Versailles in protest.

The reaction in Italy itself was supportive of its delegation. The Italian newspaper ´Idea nationale´, the organ of the nationalist Italian party would comment bitterly on the developments: ´We along, we nationalists, today have the bitter satisfaction of being able to say that we were never deluded by the idealist phantasmagoria. ´Some commanders in the occupied areas began to meddle in politics. The minister of war in Orlando´s government described plans of some generals and admirals to proclaim a republic comprising Venice, Rijeka and Dalmatia and have the duke of Aosta (the king´s cousin) to be the head of the republic. D’Annunzio, who had spoken in October 1918 of the possibility of a mutilated victory, refused to take part in this initiative as he was not chosen as the leader. By 1919, Mussolini had already founded the embryonic fascist party, which was joined by Alessandro Dudan at its initiation.

In September 1919, D’Annunzio carried out his buccaneering expedition in Rijeka, defying the treaty of Versailles by occupying the contested city. Announcing triumphantly that ´La capitale d´Italia e sul Carnaro e non sul Tevere. The Fiume expedition was in fact seen in the context of a larger design upon Dalmatia, further down the Adriatic coast. He exclaimed to the Dalmatians in Fiume: ´Brothers of Dalmatia, we have not forgotten you, we cannot forget you. With Italian troops occupying large parts of Dalmatia, fear and anxiety about another D’Annunzio movement was significant in Split.

Later that month, an attempt to seize Trogir, a small town near Split was made by Italian troops. After the Trogir expedition, D’Annunzio threatened to invade Split. This made the local population anxious, especially since the Italian navy had ordered a battle cruiser Puglia to be in the port of Split, believe that this move would strengthen the Italian position in the Paris negotiations. A tense situation developed between Croatian and Italian nationalists. It increased when Admiral Millo and the high command of the Italian navy declared their public support for D´Annunzio´s expedition to Fiume while some like Alessandro Dudan left the peace conference and joined D´Annunzio in his efforts. The British ambassador in Belgrade Sir Alben Young reports on fears of a D´Annunizian like invasion of Split.

SPLIT INCIDENT

On the eve of King Peter´s birthday in July, the Serb captain Lovric gave a strong anti-Italian speech at a political rally in Split. Clashed followed after two boys raised a Yugoslav flag near the Puglia. Two Italian officers sequestered the flag, which triggered an attack on a building by the Slavs frequented by Italians. Its sign was destroyed. Two officers of the Puglia were attacked and wounded by the crowd. Another officer sent ashore was drawn into a shooting confrontation. The Puglia organised another expedition to bring back those injured in the clashes. Now the Puglia´s captain Tomasso Giulli went ashore and began to negotiate with the Split chief of police. While they were negotiating, a bomb went off and the violence spread and in the confrontation a shot was fired and captain Giulli, another Italian sailor and a local from Split were killed. D´Annunzio, still in his little enclave in Rijeka responded to the incident with the assertion that ´Spalato e nostro grido di Guerra.´ Split is our battle cry!

The shooting of Giulli leads to Italian protests all over the Adriatic. Trieste heard of this incident on the 13th of July, where the crowd set fire to the Slovene cultural centre. According to the US historian Rusinow, 1920 saw ‘the first Fascist violence struck Europe, with the police looking on as a mob burned down the Slovene cultural centre in Trieste’. One day later, the Narodni Dom in Pazin, Istria was also incinerated. The fascist fire spread. The day after, Pazin’s seat of the newspaper ‘Pučki Prijatelj’ was also set on fire. The British foreign office reported that the Italian and the SHS state are perilously close to war as a result of the unsolved territorial question that was leading to buccaneering expeditions, shootings and arson attacks. The most intractable territorial dispute of the Paris peace conference was only (provisionally) solved by the Treaty of Rapallo in 1920. At Rappalo, Italy renounces its claims to Dalmatia (Split and Sibenik), while retaining Zadar and Lastovo, The Italians withdrew from the parts of Dalmatia they had occupied in 1921.

As a result of the danger of Italian incursions, occupations and invasions, the Dalmatia coast would, compared to the rest of the Croatian part of the SHS have an above average approval rate of unitarist, pan-Slav sentiment. Split would see the foundation of one of the largest organisations in the SHS state, the Jadranska straza (the Adriatic Guard) a cultural-political organisation that tried impress on the rest of the South Slav state the importance of the sea in the country´s trade, politics and society. Founded in 1922, the organisation had chapters set up in all parts of the country such as Pristina, Skopje, Osijek, Sarajevo and Novi Sad as well as the coastal parts. With some 180 000 members it would be one of the largest organisations in the unitary state. It was said by one of its organisers that ´the Adriatic Guard could help neutralise the bitterness in the tribal constellation of the country´. This unitary sentiment was captured in the couplet:

Za naš Jadran žrtve sve (For our Adriatic we will all sacrifice)

a nas Jadran, sinji Jadran (Our Adriatic, our blue Adriatic)

nikad I nikome ne (We will never surrender)

Did the peripheral nature of Dalmatia make its citizens fear drowning and thus seeking unitary solutions for safety sake? In the year that the Adriatic guard was founded on one side of the Adriatic, on the other side, Italian nationalists that had cut their teeth with the irredentist struggle on the Adriatic such as Alessandro Dudan would join Mussolini on his march on Rome, representing Dalmatian Italians. Relating to its politicians, the South Slav state on the other side of the Adriatic would give both the SHS state and socialist Yugoslavia its first foreign ministers in the form of Ante Trumbic and Josip Smodlaka, both who had, like Dudan, cut their teeth in the Adriatic Question´s major debates and struggles.