This is an extract from a chapter ‘Italian plans for the Eastern Adriatic’ that will be publishing in 2017 as part of a book ´The First World War in the Balkans´

‘Italy is a land which draws the breath of life from the sea. Her two lungs are the Tyrrhenian and the Adriatic…if you take the Adriatic from Italy she will be isolated and die…without possession of Dalmatia and the Curzolarias , the Adriatic will never be a sea upon which Italy can feel herself safe’

Italy’s Admiral di Revel explains Italian claims New York Times- 14 April 1918

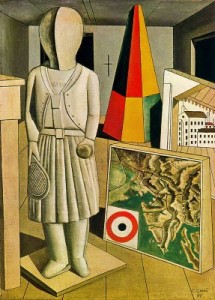

The Metaphysical Muse (figure 1), a sombre painting by the Italian Futurist artist Carlo Carrà during the First World War, reveals the social background to Italy’s wartime goal of securing strategic supremacy on the Eastern Adriatic. Painted in a mental hospital where the artist worked, the starkly drawn symbols represents Italy’s schizophrenic state on the eve of entering the First World War. In the foreground is a map of the Eastern Adriatic, with a rifle target on the bottom left corner. The map is focused on the heart of the Adriatic, Istria. According to reports from Rome in the New York Times: ‘Istria in foreign possession is a knife poised at Italy’s breast ’. Lying on the crossroads of the Balkan Peninsula, Central Europe and the Mediterranean, the Eastern Adriatic became the object of the Entente’s purchase of Italy’s services in the First World War. Carrà’s cluttered, mezzo-cubist image also represents obstacles to Italian unification, such as unbalanced industrial development, the anti-Risorgimento Vatican and the unresolved irredentism issue, all toxic tendencies that additionally led Italy to join the war to improve its vulnerable geopolitical position on the Adriatic basin. In the same months as the Sarajevo shots, Italy experienced violent revolutionary outbreaks known as ‘Red Week’. Road and bridges were blocked, railway stations demolished and phone wires cut. Numerous churches were sacked and local republics were set up. Towns like Ravenna on the Western Adriatic were cut off. The ‘Settimana Rossa’ required ‘ten thousand troops to restore order’ . The defensive nature of Italy’s adhesion to the Triple Alliance as well as social instability meant that Italy was the only great European power that declared neutrality in 1914.Less than a few months into the war, the Italian foreign minister San Gulianno noted that:

‘Italy’s major interest, and that the one most threatened, is in the Adriatic. We have no interest in other fields of the actual conflict, such as the independence of Belgium…Our enemy is Austro-Hungary and not Germany. ’

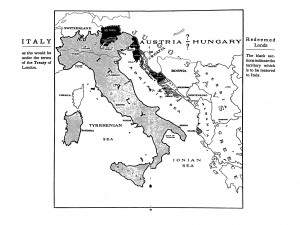

During the First World War, the maritime outposts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire would take a disproportional geopolitical significance that involved lobbying from the British Establishment and personal interventions from President Wilson. The ‘scramble for the Adriatic ’ developed between the Entente powers and the Central powers through their respective proxies the Italians and the South-Slavs. Jumping into the Entente ship in the spring of 1915, Italy launched its ‘fourth war of independence’ aiming to unify the socially divided country, ‘liberating’ the almost 800 000 irredemed Italians and securing dominance on the Adriatic. The Entente internationally legitimised Italian territorial aspirations by promising them large parts of the Eastern Adriatic through the secret treaty of London in 1915 (figure 2). Large parts of the Austrian littoral including Trieste, Istria and Dalmatia were given to Italy in order to get ‘one million bayonets ’ to switch sides and fight the Central powers.

Three years before the outbreak of the First World War, the British journalist and regional expert Robert Seton-Watson had highlighted the relevance of the Habsburg Empire’s Adriatic outlet. In his book, the British commentator prophetically claimed that:

‘The whole Eastern Adriatic coast still remains an unsolved equation in the arithmetic of Europe and its solution depends upon the course of events among the South Slavs. ‘

According to the historian Larry Wolf, Seton-Watson’s book ‘defined the South Slav question and challenged the legitimacy of the Hapsburg monarchy just as the Eastern Question challenged that of the Ottoman Empire’. Seton-Watson, just like the British government, initially supported the Danube monarchy, seeing it as a stabilizing factor in international relations:

‘The disruption of the dual monarchy would be an event equal in its far reaching consequences to the French revolution, and involving beyond all questions a general European war, of which none can foretell the issue but which might perhaps deal a fatal blow to European civilisation ’

Seton-Watson’s peacetime campaign would continue and intensify during the First World War. He became the main advocate of South Slav unity in co-operation with Italy, based on the early Risorgimento Mazzinian principles of an Italo-Slav brotherhood. Apart from Seton-Watson, bridging East and West through the Adriatic basin involved the former British attaché to Montenegro Sir Arthur Evans and the Times foreign editor Henry Wickham Steed. The Treaty of London in the long term severely damages their Gladstonian inspired liberal idea of an East-West alliance. The Adriatic was to serve as an interlocking bond between the Italians and South Slavs on a pro-liberal, anti-German platform that together with ‘Serbia guarded the gates of the gate in the east and our position in the Mediterranean and the Middle East’. Together with the Yugoslav committee that was based in London during the war, Seton-Watson engaged in energetic lobbying committee to press for a unified south-Slav state that together with Italy was to act as a shield against Pan-German expansionism and thus cut the Adriatic knot:

‘Our pledge to Italy is not in any way an insurmountable obstacle. For the Asia Minor claims which she is at this very moment pressing so keenly upon her allies might very well form the basis of a bargain. Her claim to the purely Slav province of Dalmatia would have to be abandoned and with it all attempts to keep Croats and Serbs artificially apart: but on the other hand complete naval supremacy in the Adriatic could be assured to her without any infringement of the principle of nationality, and the result would be that close of alliance between the Italians and the Yugoslavs which is so pre-eminently a British interest. ’

The reframed and revitalised liberal brotherhood of nations would replace papist, conservative and authoritarian Austria. The Slav-Italian alliance would act as chief barrier to Germanic expansionism. Italian plans for the Eastern Adriatic, legitimised by the Treaty of London, drove a wedge between the prospects of an Italy-Slav, anti-Germanic shield. The Eastern Adriatic became caught up in a tangle of transnational battles, war and diplomacy that became one of the most intractable problems of the Versailles peace conference and would cause geopolitical problems beyond the First World War.

Despite the historic claims of Italy, large parts of the Eastern Adriatic were ethnographically and linguistically Croatian and Slovene. The last Austrian census in 1910 reveals a clear majority in Dalmatia and a more balanced picture slightly in favour of the South Slavs in the Austrian littoral . Only Trieste, Western Istria and Zadar had an Italian majority. Italy’s claims for the Eastern Adriatic rested partially on historic and cultural arguments. The notion of jus primis ocupantis went back to antiquity. The provinces had all been part of Roman Empire, with several emperors being born there including Diocletian, whose palace at Split even in 1914 seemed to stand as an architecturally enduring imprint of the Italian civilità. During the early modern period, the centuries-long dominance of the Venetian empire on the Eastern Adriatic gave major coastal cities like Zadar, Trogir and Korčula a distinct imprint of il Serenissima.

Yet the Eastern Adriatic since the fall of the Roman Empire had been the junction of Europe’s three largest people, Italian, German and Slav, all with historic claims to the region. In the Middle Ages, Dante’s Inferno rhapsodised that the Eastern Adriatic was: ‘where Italy bathes her boundaries ’. Dalmatia, the ‘firstborn province ’ of Venice, had a special place in the Italian consciousness, having been romanticised as an exotic paradise by the Venetian dramatist Carlo Goldoni . In 1910, Trieste had a bigger Slovene population than Ljubljana. One of Slovenia’s greatest novelists Ivan Cankar famously stated that: ‘If Ljubljana was the heart of the Slovenes, Trieste was its lungs.’ Having been under Habsburg control since the 14th century, the largest Austrian port still had a thriving German community in organised in the Schillerverein and saw Trieste as their ‘bridge to the Adriatic’.

Since the mid-19th century, the Italian unification movement had led to regular wars between Austria and the nascent Apennine state. Under the leadership of the house of Savoy, Italy had pecked at the Austrian eagle’s territory throughout the 19th century, taking Lombardy in 1859 and Veneto in 1866 in what Italian historiography would call the second and third wars of independence. Use of South-Slav troops to quell pro-unification risings in Italy meant that strong antipathy had developed between South Slavs and Italians as can be seen by the negative portrayal of the Croats in Giusti’s Risorgimento poem Sant’ Ambrogio. The First World War as a prolongation of the Risorgimento can be seen in an image drawn at the time of Italy’s entry into the war. The caption reads: ‘After centuries of martyrdom, Italy breaks her chains’ (figure 3). It demonstrates how the ‘fourth war of independence’ would finally complete Italian unity. It shows the Italian king Victor Emanuel III leading a successful cavalry charge of Italian army through the Austrian border to rescue the irredemed provinces Trieste, Dalmatia, Istria and Trent. The dashingly romantic scene is observed by Garibaldi and other historical figures who fought for Italian unification. Italian plans for the Eastern Adriatic in the First World War were presented as a natural finale of the revolutionary ripples of the emancipatory Risorgimento. The movement for unity had been scuttled by the Austrian navy off shores of Vis in 1866 as the Austrians in a rare wartime victory halted the Italian advance. In negotiations about transferring the Eastern Adriatic to Italian hands in 1915, the Italian ambassador refers to 1866 as the key date as recalled by the British foreign secretary Sir Edward Grey:

‘He spoke most strongly of the claim of Italy to the coast of Dalmatia and the islands. He said that for six centuries it had belonged to Venice and, till 1866, was Italian by nationality. If, since that date, the Italian element had been weakened, it was owing to the deliberate policy of Austria in introducing a Slav element .

Since then, Italian influence in the Eastern Adriatic parts of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy would decrease. Austria forbade its Slav citizens to study in Italy, introduced a more liberal constitution in 1867 and founded a Croatian language university in Zagreb in 1874. As more south Slavs became educated in their mother tongue, the Slavic rebirth intensified culturally as well as politically. As the 19th century wore on, the number of Italian controlled municipalities in Dalmatia went from 84 in 1861 to 1 in 1914. In 1909, Italian was replaced by Croatian as an official language, leading many Italians to fear for the future of Italian culture on the Eastern Adriatic. The Zadar born professor of Italian at University College London outlined the reasons for Italy’s intervention in an article written in 1915:

“The reasons of the present Italian war, as well as the open affirmation of Italian aspirations and rights, are deeply rooted in those ‘sacrifices’ of the new and not yet completed nation, as well as in the long and indescribable sufferings of the Italians on the eastern shore of the Adriatic – and more especially of the Italians of Dalmatia – through the iniquitous denationalizing policy pursued by Austria.”

According to Italian historians of the Adriatic: ‘Austria’s domestic policy and the rise of Croatian nationalism had turned the Italian and Italo-Slav Dalmatians into a persecuted minority whose fundamental cultural and national rights were oppressed: the right to a free public school in their own language, the right to cultural and linguistic freedom and the recognition of an equality of treatment with respect to the majority of the country[1].’ The undoubted advance of the Slav element in the monarchy had provoked amongst the Italians of the Eastern Adriatic a quasi-pathological hypertension of national sentiment. The situation had changed for the worse in the years since the nineteenth century for if ‘Cavour, Mamiani and Mazzini could be content with borders in the Alps, for their political heirs such as Salandra, Sonnino and Giolitti, the Habsburg conquest of Bosnia, the end of Ottoman rule in the Balkans and the worsening living conditions’ of the Eastern Adriatic Italians were all motives that drove the new generation of Italian politicians to demand large parts of the Eastern Adriatic, beyond the lines of nationality.[2]’

Italian War Aims

In 1915, hundreds of thousands of Italians still lived in the territories from the Brenner Pass to the bay of Kotor. Contemporary Italian posters (figure 4) shows Italy being baited by the different European powers by offers of different territories claimed by Italian irredentism. This included Garibaldi’s birthplace Nice, while Tunisia had more Italians living in it that Dalmatia. Supporters of the Risorgimento on the Eastern Adriatic argued that it was the bulwark of Latinity and shielded the West from Slav barbarism. At their most extreme, they propagated a more radical, anti-Slav and maximalist wing of Italian irredentism. Ruggero Timeus, one of two thousand Italians from the Eastern Adriatic that fought for Italy in the war, wrote in his novel ‘Trieste’ that ‘Italy must conquer Trieste not merely in terms of completing national unity but in expectation of imperial expansion towards the Balkan peninsula. [3]

Aiming for Trieste was not merely symbolic, since it was one of the busiest in Europe in the first decades of last century. If Hamburg was the door to the World, Trieste was central Europe’s opening to the Mediterranean, the third entry to the Suez Canal and the route to the Far East. Therefore, the economic advantage of owning the Eastern Adriatic and its busiest ports at the top figured significantly in Italian aspirations. Nevertheless, despite the economic element, Timeus’ writing carry an apocalyptic edge regarding the Slav-Italian national struggle: ‘In Istria the struggle is a fateful inevitability that can only be brought to conclusion by a complete disappearance of one of the two races that are fighting[4].’

A contemporary Italian postcard entitled ‘The Italian war aims’ (figure 5) shows a fort with three doors. The doors are labelled with the irredeemed provinces of Trent, Trieste and Dalmatia, with the first two being guarded by soldiers and the last being guarded by a sailor. The caption states that ‘The Alps and the Adriatic coast are our front porch’. Italian neutrality at the outbreak of the war made a significant amount of irredentist interventionists write articles to encourage Italy to intervene on the side of the Entente in order to secure the vulnerable position of Italy on the Eastern Adriatic. Since the Austrian annexation of Bosnia, Italian defence and political experts had believed that ‘control of Dalmatia was crucial to determining the outcome of military conflicts in the Adriatic.[5]’ Those involved in this campaign included nationalists such as the poet-soldier Gabrielle d’Annunzio and the parliamentary representative for Venice, Foscari. In a newspaper article, Foscari explained Italy’s aims and ambitions for the Eastern Adriatic, focusing on a mixture of historical, geological and strategic reasons why Dalmatia needs to be in Italy’s hands for: ‘in the hands of others, it is a continual and grave threat to our heart.[6]’

The Italian Admiral Thaon di Revel would later outline the naval dimensions regarding Italy’s strategic vulnerability in an article for the New York Times. The admiral points out the serious disadvantages for the Italian naval forces due to the dearth of naval ports that are vastly inferior on the Western Adriatic compared to the sheltered, deeper lying and strategically superior ports of the Eastern Adriatic.[7]

Italian claims on the other side of the Adriatic coincided almost exactly with the borders of Venetian Dalmatia at the time of the Treaty of Passarowitz in 1718. With the request for Istria and Valona, Italy’s ultimate aim in the First World was to turn the Adriatic back into the Gulf of Venice and thus into an Italian lake. The first Italian action in the First World War was to occupy the island of Saseno, near the Albanian coastal town of Valona on the 30 October 1914. This minor strategic key to the Adriatic began the attempt to turn the Adriatic into an Italian lake.

By taking the port of Valona, Italy hoped to shut off the Central powers supply lines by corking the Adriatic which was a major supply route for Austro-Hungary. By offering Italy large parts of the Eastern Adriatic, the Entente hoped to drive a wedge between the Triple Alliance, breaking the Central power’s stranglehold on the Adriatic and thus prevent Germany from advancing south. Italy’s plans for the Eastern Adriatic would have allowed them to hold the keys of the Adriatic and be secure from all military attack behind two impregnable mountain walls on the northern Alps and the Dinaric Alps. The Trieste born journalist Tamaro, in a tract for the Royal Italian geographic society explained the need for the treaty as ‘purely defensive.’[8]

Italy had declared neutrality as it claimed that its intervention would only occur in the case of a defensive war. Only after the French successful riposte of the Germans in the West and Austrian defeat in the East did the Italians begin to consider the possibility of a war against the Danube Monarchy. Italian neutrality did not go unnoticed by the press in the UK. The British newspaper, The Spectator noted in an editorial that Italy could not expect to ‘have a great say in the remaking of Europe if she did not purchase her right through sacrifice’[9] via military contributions.

Less than two months after the Spectator article, the Serbian parliament passed the Niš resolution declaring that Serbia’s war aim was ‘the liberation and unification of all our brother Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.’ This meant that Serbia and Italy were competing with each other for territories with a South Slav population. An Italian postcard (figure 6) from 1915 shows a dialogue in a hotel between the Italian King and a Serb soldier. The caption underneath shows the dialogue with the Serb soldier asking: ‘Your majesty, Russia sends me for a nice room in Dalmatia with a view of the Adriatic’. This is an allusion to Serb claims on the Eastern Adriatic, to which the Italian King responds that ‘all the rooms are taken, but the corridor remains.’ In this way, the Eastern Adriatic became a point of discord between the Entente, whose need for future larger allies like Italy meant going behind the back of present smaller ones like Serbia. Gathering more allies became a pressing issue for the Entente as the war dragged on.

The start of 1915 showed the Entente that the war was not going to be over by Christmas. On the rain soaked fields of the Western front, khaki-clad British troops became bogged down in muddy trenches. The ‘Empire on which the sun never set’ found its blindly vigorous enthusiasm for war blunt against the towering Teutonic enemy. Worse, Britannia’s rule of the waves was no longer absolute, as German submarines sank British battleships like the HMS Formidable. Even the ‘fortress built by nature’ was now regularly penetrated by German Zeppelins, whose bombings in January 1915 caused Britain’s first civilian deaths in Great Yarmouth and King’s Lynn. The Ottoman Empire, who Britain had defended during its previous continental engagement in the Crimea, was now fighting alongside the Central Powers. The sick man of Europe was being helped into recovery by the Prussian pernicketiness of general Liman von Sanders. Calling for ‘Deutschland, Deutschland über Allah’, the fear of tri-continental dominance via the Berlin-Bagdad axis sent a shiver down the spine of the usually placid British colonial governors.

Italy and the Entente

It was seen as vital to win over Italy as rapidly as possible at almost any cost, even if an additional alliance agreement was ‘a glaring departure from the principle of nationality[10]’. In this way, the Entente would act as a magnet for the other neutral states such as Bulgaria, Romania and Greece and thus start encircling the Central powers and blocking their route to the East. Indeed, the fact that neutral countries like the Ottoman Empire had joined the Central Powers was seen as a ‘great disaster of Allied diplomacy.[11]’ Thus it was Italy’s plans for the Eastern Adriatic that were seen as more important as it was the only neutral remaining great power that could bring an extra ‘one million bayonets[12]’ meaning that Serbia was kept in the dark from the secret negotiations about the Eastern Adriatic.

The negotiations for Italy’s entry into the war can be read in the official correspondence between Russia, France and Italy. Politicians like the future Prime Minister Lloyd George constantly advocated ‘bringing Germany down by the process of knocking the props under her[13].’ The Entente believed that the unbreakable Western Front could be turned by an attack through Italy. London wanted to prevent Germany from advancing south through breaking the Triple Alliance’s decade’s long stranglehold on the Adriatic.

Secret documents of the UK foreign office show that by the beginning of March 1915, most[14] of the demands of the Italian plans for the Eastern Adriatic were already in place[15], including demands for a loan to be floated on the London stock market and a promise to keep the Vatican out of future negotiations. Private and secret correspondence at the foreign office between the British foreign secretary Sir Grey and the British ambassadors in Russia and France, besides affirming Italian claims to the cities of Dalmatia, reports that Italy’s principle motivation of entry into the war was to remove ‘the intolerable situation of inferiority in the Adriatic vis-à-vis Austria[16].’Grey adds that Italy would not accept replacing Austrian dominance with Slav dominance of the Adriatic.

Sir Edward Grey and the British ambassadors in the Entente capitals demonstrated a hard-nosed diplomatic pragmatism vis-à-vis the principle of nationality which was seen as secondary compared to winning the war. The Italian alliance was said to be the ‘tipping point’ with officials at the foreign office predicting that it was ‘likely to decide the war in three months.[17]’The British foreign secretary in his correspondence with the British ambassadors in Paris and Moscow agrees that the Italian claim is more strategic rather than ethnic for the coasts and islands of Dalmatia provides Austria with an ‘ideal haven for submarines.[18]’In correspondence with the British ambassador in Italy Rome, Sir Rennel Rodd, Grey admits that he sympathises with the Italian position of vulnerability to naval danger.[19]The negotiations lasted several weeks, with Grey soon agreeing in principle to Italian demands subject to detail[20]. The broadly sympathetic British attitude towards Italian claims can be seen in the letter of Rodd, who recognises Italy’s need to ‘make the Adriatic her naval base and acquiring absolute security for the future of the Adriatic.’[21]

The British felt that Italian intervention would decisively change the course of the war and that victory was more important than the principle of nationality. In an old-style diplomatic game, the British foreign secretary felt that diplomatic success in getting Italy on side would set an example to others such as Romania, in an attempt to encircle the Central powers from both sides. This is shown in his correspondence with the British representatives in the Entente capitals:

Italian co-operation will decide that of Romania and probably of some other neutral states. It will be the turning point of the war and will greatly hasted a successful conclusion[22]. … I am informed that the Rumanian attitude is closely associated with Italy, and failure of negotiations with Italy will cause a set-back in Rumania.[23] … It would, in our opinion, be a thousand pities to lose the great prize of Italian co-operation for the sake of so small a difference. I understand the French also hold this view very strongly.[24]

The fragility of the Entente was confirmed a few days later by Sir Rodd in a letter:

We are therefore up to a critical issue. We can have immediate co-operation of Italy, ensuring, I believe the co-operation of Romania and affecting that of all the other Balkan states, with great results if we do not insist on applying to her acquisitions the very unreliable condition of neutralisation, and if we agree to her occupation of Cursola islands with Sabbioncello, which would be neutralised together with Serb coast. Price of Italian co-operation involves sacrifice of Dalmatia.[25]

A major cause of disagreement with Russia was what to do with the southern Dalmatian coast. Standing in the middle of the Adriatic, the strategically vital harbours around the Curzolari islands were close to a potential maritime outlet for Serbia. This was shown by a map produced by Sir Arthur Evans in Seton-Watson’s weekly newspaper The New Europe (figure 7). Disagreements arose due to the question of whether some of southern Dalmatia should be given to Italy, shared in some way between Serbia and Italy or neutralised. The Russian ambassador Sazonov, despite accepting the document in principle, insists on Serbian access to Dalmatia:

In order for Serbia to have access to the sea in proportion to its territory, it would be necessary to give her the Dalmatian coast with the adjacent islands, from the mouth of the Krka up to the Montenegrin frontier, which would pass probably somewhere a bit north of Ragusa[26].

Russia was seen to be pulling the strings behind Serbia’s drive towards an outlet to the sea and potentially challenging Italy’s aspirations for the Eastern Adriatic. Italian plans for the Eastern Adriatic would cause disagreements between the allies, with the Russians in particular keen to maintain Serbia’s right to access the Adriatic, which she had been denied at the end of the last Balkan wars. Fear of Adriatic ports in Serb hands being turned into Russian ports[27] is mentioned by the Italian foreign minister to Sir Rennel Rodd. It was not an enlarged Serbia that Sonnino feared but Russia, who ‘if she obtains control at Constantinople may become in future the leading naval power in the Mediterranean.[28]’ Eventually, with the pressure growing from the Entente, Italy withdrew its demands for the town of Split and the Pelješac peninsula. Russian obstinacy in the face of Entente negotiations can be explained by the Tsar’s connections to Montenegrin royal family and still existent pan-Slavic sentiment within the largest Slav country. Despite the adjustment, the treaty of London has been described as a ‘triumph of Italian diplomacy[29]’ due to Italy’s territorial aspirations being grounded in an international Treaty that would guarantee gains made in war and went beyond the ‘minimum expectations of the Italian ruling class.[30]’

Italy’s plans for the Eastern Adriatic benefitted from a pronounced Italophile section within the British establishment who had been raised in the spirit of the classics, the Grand Tour and the shining relics of the Apennine peninsula’s past. Britain’s affinity with Italy went back to Venetian days. Shakespeare had marvelled Venetian society in his plays. James I had written a pamphlet in defence of Venice, which like England was a constitutional, maritime and mercantile empire fortified by nature. The British Empire, like Venice was fortified by nature, commercially based and anti-papist. The wistful nostalgic poetry of William Wordsworth, lamenting the extinction of the Venetian republic[31] shows the cultural imprint that an early-modern, Italian speaking and trans Adriatic entity had made on the British conscience. In the 19th century, the city of the lagoons continued to capture the British imagination as the wistful Venetophilism of Britons like Shelley, Turner and Ruskin demonstrate. This affinity developed a new élan during Italian reunification that connected the previous affinity with Venice with a certain strand of British Whig politics that supported intervention in European causes. Like Byron a few generations earlier, the historian Trevelyan the elder had gone south in order to fight for liberty in a war of independence against a reactionary empire. Parts of the liberal party, following the anti-Austrian heritage of Gladstone, would have agreed with the Italian and pro-Italian population along the Eastern Adriatic in seeing the Risorgimento an anti-clerical, liberal and progressive movement and thus the last libretto of the Risorgimento. Support in Britain for Italian plans included the Saturday Review, the Pall Mall Gazette, the Cambridge Magazine and the Spectator, which celebrated the entry of Italy into the war, alluding to the liberal elements present in the Risorgimento, the significant armed forces at its disposal and the vital morale booster for the Entente:

Italy has joined the forces of freedom with whom her heart has long been beating. It is her right and natural place. Even if the Italian Army were defeated, it would have occupied the attention of some half-million of Austro-German soldiers. The increment of moral power which Italy brings to us is enormous. The spirit of the Risorgimento is still alive[32].

Nevertheless, not everyone in the UK supported Italy and its imperialist aspirations for the Adriatic. Parallel to the secret negotiations with the Italians, at London’s King’s College, Seton Watson was appealing to the British public to support Serbian claims in the Eastern Adriatic, challenging with it Italian plans for the Eastern Adriatic:

Serb and Croat, it must be remembered, are two names for one and the same language… Serbia is not merely fighting for her independence and existence, but also for the liberation of her kinsmen, the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes of Austria-Hungary, and for the realization of National Unity. Hence the real question at issue is the future of eleven millions of people, inhabiting the whole eastern side of the Adriatic, from sixty miles north of Trieste as far as the Albanian mountains[33].

In the lecture, Seton-Watson lays the foundation for the course of South Slav unity that would develop with the initiative and assistance of numerous British South Slav supporters who despite being Italophiles[34], believed in the South Slav link as being the crucial bridge between the East and the West and the Adriatic its most intimate contact point. Seton-Watson, supported by the former British attaché to Montenegro, Sir Arthur Evans and the Times foreign editor Wickham Steed now saw South Slav unity around Serbia as the only possibility for saving the Adriatic coast from going from one alien rule to another.

Seton-Watson and the Treaty of London

Despite being a flagrant violation of the principle of nationality, the Treaty of London was very much a product of its time. Apart from promises made to Italy, the Entente ‘sought in vain to lure still neutral Bulgaria with Serbian land in Macedonia, while the following year they promised Romania the Hungarian territory of Banat, which Serbia wanted for itself[35].’

Three days before the Treaty of London was signed, Seton-Watson sent a long letter complaining about the treaty to the London Times, emphasising that the treaty is going against the interests of Britain’s allies in the war as ‘Italy’s claim to replace Austria on the Eastern Adriatic cannot be realised unless she annexes at least a million Slavs.’[36]

Seton-Watson had travelled around the Eastern Adriatic and had made friends with numerous local politicians and journalists such as the Split mayor Trumbić, the journalist Supilo and parliamentary representatives of Eastern Adriatic regions like Smodlaka and Lupis-Vukić. These public figures from the Eastern Adriatic were frustrated with the slow pace of political reform in the Danube monarchy and were excited by the prospect of the Serbo-Croatian coalition. Restricted though it was to one province the pan-Slavic parliamentary co-operation in Dalmatia seemed proof to Seton-Watson that an alliance between Serbs and Croats was possible on a national scale which together with an Italo-Slav alliance would replace hostile Teutonic Mitteleuropa with a more benign political order friendly to the Atlanticist interests of the Entente:

It was from Italy that the Croat and Serb leaders in Dalmatia took their inspiration, alike in political thought and literature. Today their chief aim is an intimate understanding between Slavs and Italians, as the sole basis upon which they can hope to resist the German Drang nach Ostern … but this understanding cannot be purchased at the expense of national suicide.[37]

Inspired by nineteenth-century Gladstonian liberalism, Seton-Watson attempted throughout the war to point to a possibility of the Italo-Slav alliance as a barrier to German expansion towards the South and East that could harm the alliance of Slav and Latin that could form a strong anti-German pillar in this part of Europe.

Seton-Watson eventually helped establish the London School of Slavonic Studies as an academic institution for supporting long term British ascendancy in South-Eastern Europe. He became the chief intermediary between the foreign office and the nationalities of the Habsburg Empire though his friends in the Yugoslav committee.

Campaigning against Italian plans for the Eastern Adriatic, Seton-Watson highlights the importance of not betraying potential allies in an area where millions of anti-Austrian Slavs could yet rush to the Entente colours. Yet because of the Treaty of London, Seton-Watson claimed that South Slav loyalty to the Habsburgs would increase as they preferred an Austrian to an Italian regime.

To all the South Slavs of Austro-Hungary this war has been one long and hideous martyrdom. There is one means, and only one means of rendering it popular. It is that Italy should engage in the war with the object of annexing the Dalmatian coast and islands. In that event, the entire population will offer a desperate resistance to the Italian invader, and Austria-Hungary, by representing the Entente powers as the inspirers of an anti-Slav conspiracy, will have one last chance of rallying her disaffected southern Slav populations.[38]

Seton-Watson’s prediction proved to be right. In response to Italian irredentist claims on the Eastern Adriatic, Austro-Hungary galvanized its South Slav population by sending the South-Slav general Svetozar Borojević to lead the defence of the realm. Borojević, the only South Slav who became a field Marshall in the Hapsburg army, acted as an extra motivator for South-Slavs to fight what was perceived as a perfidious invasion of their own territories. The field marshal’s success in leading the Habsburg army to twelve victories against the Italians during the war gained him the nickname the ‘lion of Isonzo’. Boroević became an honorary citizen of over seventy different towns and cities on the Italo-Slav borderlands such as Ljubljana, Varaždin and Karlovac.

Seton-Watson’s letter to the Times also points out how the Treaty of London would damage the reputation of the Entente, as it would be a counterproductive measure only serving the interests of the Central Powers. Moreover, he outlines his vision of the South Slavs as intermediaries between Britain and Russia, whose betrayal would be a betrayal of all the principles and aims that the Entente stands for:

Those who advocate an Italian Dalmatia are consciously or unconsciously playing the game of the Central powers…The South Slavs and it should be added the Bohemians are our natural allies, as the intermediaries between Britain and Russia, between Britain and the great Slavonic world…if we abandon them, we deliberately turn our back upon the future and renounce the principles of justice, liberty and nationality in favour of those motives of racial dominance and strategic grab which inspire the German and Magyar authors of this war.[39]

London became the embryo of important post-Hapsburg institutions that were to shape Austro-Hungarian succession including the School of Slavonic studies, Seton-Watson’s weekly newspaper New Europe and the Yugoslav committee that spent most of the First World War in the British capital. Seton-Watson set himself a formidable task of trying to stave off Italy’s claims to the Eastern Adriatic, keep balance between the different visions of the South Slav future but also to reconcile the Italians and the South Slavs. He felt that only a Slavo-Italian liberal alliance that had seen the light of day in 19th century Adriatic multinationalism[40] could successfully defeat and replace, papist, conservative and authoritarian Austria. Recent research done by Italian historian Cattaruza has argued that elements of the Italian establishment such as Gaetano Salvemini and Leonida Bissolati entered the war on a platform of national self-determination of all the people in the Hapsburg monarchy based on a fraternity between Italy and the Slavs. This re-proposal of the early years of the Risorgimento uses Mazzinian ideas of politics that conciliates national sentiment with international solidarity. In a twenty five page long memo called the Adriatic problem, Seton-Watson claims that Italian plans for the Eastern Adriatic are a deviation from the Italian unity and independence project, noting that the foreign secretary: ‘Baron Sonnino…his utter departure from the spirit of the Risorgimento[41]’.

Lobbying against the Treaty of London became a major priority for Seton-Watson as it had driven a wedge in the possibilities of an Italo-Slav with the Slavs as the force of aggregation between East and West. Spending a lot of his own money, Seton-Watson’s newspaper New Europe dealt with European affairs with a special focus on Central Europe and the Balkans. In a tireless advocacy campaign, his letters to newspapers such as the Nation reveal a criticism of the Entente for their collusion with Italian plans for the Eastern Adriatic as being harmful to long-term interests of everyone:

A close understanding between Italy and the South Slavs and Romania is an essential preliminary to any lasting settlement of the Balkan and Adriatic problems, and to the reconstruction of South Eastern Europe on healthy national and economic lines; and if Dalmatia falls to Italy such an understanding will be ipso facto impossible.[42]

Seton-Watson’s private notes reveal an admiration for the nineteenth-century concept of Adriatic multinationalism. Seton-Watson’s idea of a revitalisation of a Slavo-Italian alliance was based on the fact that early Mazzini and Nikola Tommaseo considered Slavs as allies in the struggle for national and political emancipation against Austria. The British journalist private notes contain a collection of the quotes of the major figures of Adriatic multinationalism such as Mazzini, who claimed in the nineteenth century that: ‘our future political and economic power rest in an alliance with Jugoslav, Daco-Roman and Hellenic people’[43] while the contemporary chairman of the Yugoslav committee Trumbić mentioned in 1903 that ‘the Adriatic sea ought to unite Croats and Italians[44]’.

The Yugoslav Committee and South Slav Unity

The Yugoslav committee, set up and financed initially ‘on the initiative of Nikola Pašić’[45], the Serb prime minister, included Seton-Watsons friends from the Eastern Adriatic Supilo, Trumbić and Meštrović. Supilo’s mother was Italian and he corresponded with Seton-Watson in Italian on some occasions. All would have been aware of the Italian unification paradigm and nineteenth-century Adriatic multinationalism. In the newspapers of the Yugoslav committee, published in Geneva and London, the pro-Slav orientations of Italian founding fathers such as Mazzini testify to sympathy with the Italo-Slav alliance that could be reborn in a new European order. In one of the issues of the Yugoslav committee’s newspapers there is a whole page dedicated to Mazzini and other Risorgimento leaders positive attitudes towards an Italo-Slav alliance, with the Slavs playing a partner role: ‘The Turkish and the Austrian empire are condemned to an inevitable death. The duty falls on Italy to hasten this death. The spear that will do this lies in the hands of the Slavs[46].’

One of the first things that the Yugoslav committee did was publish a program that it addressed to the British people in the Times newspaper. Translated by Seton-Watson, it appealed deliberately against the Treaty of London and Italian plans for the Eastern Adriatic as well as embraces the principle of nationality and the ideas of South Slav unity:

The Jugoslavs inhabit the following countries, Kingdoms of Serbia and Montenegro; the Triune kingdom of Croatia, Slavonia and Dalmatia (with Fiume and district)… to transfer even portions of them to another rule, would be a flagrant violation of our ethnographical, geographical and economic unity.[47]

Together with their British supporters, the Yugoslav committee contributed to the intense lobbying campaign against Italy’s plans for the Eastern Adriatic. In a telegram to the foreign office, Supilo demonstrates an eloquent argument against the Treaty of London, indicating the inherent and unjust hypocrisy relating to British reasons for entering the war

A terrible injustice will be done to our cultured and civilized nation if Italy is allowed to occupy our shores. Such a crime against our nation on the Adriatic could only be dictated by the brutal force of the stronger, in the same way as German militarism occupied Belgium. It is impossible to believe that Europe, which rose against Germany for this very reason, should now allow Italy to enforce the principle of the stronger against our compact and overwhelming majority on the Adriatic coast. By such a proceeding civilized Europe would only contradict all her own assurances to Belgium: for Italy does not enter to liberate but to conquer the territory and towns of our nation.[48]

Despite the best efforts of Seton-Watson and the Yugoslav Committee, the strong Italian lobbying led by Italy sympathizers at major universities meant that the British public knew little about the Eastern Adriatic ethnographic realities. An extract from contemporary media tendentiously and deliberately refers to the Eastern Adriatic, as ‘Italy’s other shore’. The article shows the major Roman remains in the Adriatic coastal towns of Split, Pula, Zadar and Kotor, noting that:

If you want a spectacle of beauty… you must slip out of the lagoons of Venice and steam across the Adriatic to what was once, and will be again, Italy’s other shore, Dalmatia. Some of it she only lost a hundred years ago, while in other portions the Lion of St Mark is still rampant, as in Zara.[49]

The Yugoslav Committee and their supporters in the UK wanted to demonstrate to the public how the South Slavs were a viable ally the Eastern Adriatic. In a successful public relations exercise, a member of the Yugoslav committee Ivan Mestrović’s sculptures would be exhibited at London’s Victoria and Albert museum. Mestrović as a living symbol of South Slav unity was able to connect Eastern themes of heroic resistance, sacrifice and struggle for freedom through a Western medium, sculpture. This symbolically set in stone the unity between East and West. The Dalmatian sculptor ideally captured the new Yugoslav synthesis ideally, since it took Eastern themes of Serb heroic epics about Kosovo yet presented them in a western medium which had been well developed in the Eastern Adriatic cities. In this way, the gap between Oriental Serbs and Occidental Croats was bridged together through the works of Mestrović. The exhibition opened by the undersecretary of foreign affairs, Lord Robert Cecil, highlighted the successful intermediary element of Meštrović’s artworks: ‘Ivan Mestrović can be said to have grasped the significance of the soul of the Slav and to have translated it into imperishable marble[50]’

The exhibition brought the Balkans and Dalmatia closer to Europe, with Meštrović’s work acting as a keystone between the East and West. The intellectual and cultural reconceptualization of the South Slavs as a link in the bridge between East and West was thus given public prominence as reviews described him as: ‘A southern Slav who, racially, stands mid-way between Eastern and Western civilization [51]’. The message to the British public was evident, a Slav revitalization of Europe was possible from Teutonic, militaristic, materialistic might. ‘A better propaganda cannot be invented’ according to Seton-Watson who saw the exhibition as a sign of Jugoslav unity through an artist from the Eastern Adriatic. In many ways, the exhibition was a resounding success, although it did reveal the omnipresent cracks in South Slav unity. The Serbian ambassador in London, Bosković had boycotted the exhibition due to Mestrović’s refusal to call himself a Serb. The Serb ambassador objected to the brochure of the exhibition being called ‘Mestrović the Yugoslav artist’ demanding that it be changed to Serb. Prof Cvijić, in the name of Bosković, the Serb ambassador, attempted to persuade Mestrović, who is said to have answered: ‘with this Yugoslav, I wanted to say both, i.e. that we are one’.

Serbia did not see the Yugoslav committee as a legitimate partner due to an inherent distrust of South Slav politicians from Austro-Hungary who were seen as contaminated by Teutonism, Papism and Western ideas. Pašić, despite having helped set up the Yugoslav committee, had ‘objected initially to the name Yugoslav committee, claiming that an enlarged or greater Serbia would be preferable as Serbia already had a status as an ally[52]’. The Serbian prime, who had seen in their lifetimes Serbia double in size through territorial extractions from the Ottoman Empire, saw no reason why similar extractions were not possible from Austria without resorting to compromise. As a result, Serbian attitudes towards the Eastern Adriatic issue were ambivalent at best and indifferent at worst. Despite the Niš declaration of 1914 committing Serbia to freeing all of the South Slavs, the Eastern Adriatic hardly appeared in their plans. Trevelyan and Seton-Watson had made journey to Serbia in December 1914. During the unofficial visit, Seton-Watson, in conversation with the king, having been told that he ‘would sooner lose Bosnia than give up Macedonia[53],’ has the opportunity to try to persuade him towards engaging more towards the Eastern Adriatic: ‘We hope that Serbia will turn her eyes more towards the West (pointing to Bosnia and Dalmatia on map) and less to the East. For Macedonia represents the past and Dalmatia the future for you.[54]’

In spite of the overtures of Britain’s South Slav supporters, it seems that Serbia was more concerned with the other fronts and gave little consideration to the Eastern Adriatic. Mestrović recalls a 1915 conversation with the Serb foreign minister Jovanović that dismissed the Eastern Adriatic as almost irrelevant: ‘We want to get Bosnia and an exit to the sea, the rest does not concern us, we will have time later…, Bosnia and Dubrovnik, the rest of the coast shall go to the Italians and Croatia shall remain with Hungary.[55]

A letter from the British ambassador in Russia, Sir Buchanan a few days before Italy’s entry into the war reports of two Serbian professors being receive by the minister of foreign affairs: ‘They spoke to him about Serbian aspirations in Dalmatia and the Banat insisting strongly on the importance of latter to Serbia[56]’. Serbia’s indifferent attitude to the Eastern Adriatic is also revealed in a document sent by the Serb Royal family to the British foreign office. The letter spends seven pages justifying the right of Serbia to the Banat and a mere two sentences on the Eastern Adriatic, noting that: ‘Italy claims Trieste, Gorica, Pola for reasons of security, of a danger, which does not exist[57]’

Serbia’s recent victories in Macedonia and Belgrade’s vulnerable position on the Austrian border meant that Serbia was more interested in securing its south-eastern and northern border as a buffer against future Austrian attacks rather than concerns about a maritime outlet. The major Serbian politicians, despite knowing the value of the Eastern Adriatic to the Yugoslav committee were not concerned. In April 1916, Pašić gave an announcement to Italian newspaper Corriera della Sera correspondent in St Petersburg, promising the Italians the predominant position on the Eastern Adriatic:

There are no serious misunderstandings between the Serbs and the Italians… we Serbs cannot deny the clear right of Italy to hegemony on the shores of the Adriatic.[58]

The excessively pro-Serbian attitude that was making its presence felt in the Yugoslav committee eventually led one of its most capable members, Frano Supilo to resign in 1916, citing numerous reasons including lack of consideration for the Eastern Adriatic from Serbian politicians, who were ready to let Croatia be divided in the twentieth century like Poland in the eighteenth.

1917 saw major changes to the international situation firstly due to the February Revolution in Russia. Losing substantial backing from its major patron, Serbia was forced to become more co-operative with the Yugoslav committee. A blueprint for a South Slav state was signed on the Eastern Adriatic, on the Greek island of Corfu in July 1917. In the eyes of the British south Slav protagonists, this appeared as ‘triumphant proof of harmony and agreement between pan-Serb and exiled Yugoslavs[59]’. Seton-Watson felt that only a strong South Slav state could defend the Eastern Adriatic against Italian threats. With the institutionalisation of the South Slav Union sacrée and the Italian heavy defeat at the battle of Caporetto in November 1917 meant that the Italians were prepared to negotiate with the representatives of the South Slavs.

The meetings that were supposed to establish Italo-Slav unity first took place at Steed’s house in London in December 1917. The Italian delegation, though not with an official mandate, containing officers and politicians with strong influence in Rome. It was agreed that Austro-Hungary needed to be dismembered in order for the Adriatic question to be solved. An Italian general Borghese indicated that Italian claims for the Eastern Adriatic were in fact not as strategic as the politicians in Rome indicated, admitting Slav predominance in most of the Eastern Adriatic:

These are Slav parts, all except for Trieste, indeed the suburbs of Trieste are all Slavs. I was there. I was on the frontline in Gorizia. Nobody wants us there and they are all against us…We need more space for our large population, this cannot be Dalmatia, nor Istria but somewhere in Africa. If the Allies are well meaning, they should give us something.[60]

After encouragement, it was agreed in principle that ‘Italo-Jugoslav friendship was the bulwark of European peace[61]’. This was given further impetus in January 1918 as two of Wilson’s fourteen points specifically applied to the situation in the Eastern Adriatic. Point nine spoke of ‘a readjustment of the frontiers of Italy along clearly recognizable lines of nationality’. Point 10 indicated that ‘the peoples of Austria-Hungary, whose place we wish to see safeguarded and assured, should be accorded the freest possible opportunity of autonomous development.’ This created alarm in Italy, where calls emerged from the Italian department of propaganda to: ‘at once reach an agreement with the Yugoslavs and summon a congress of the nations subject to the Habsburgs[62]’. In March 1918, Italian parliamentary representative Torre signed an agreement with Trumbić that stated that the future border between a South Slav and an Italian state would be decided democratically:

The representatives of the Italian and Yugoslav peoples agree in particular to engage themselves to settle amicably, in the interest of good and sincere relations in future between the two peoples, the various territorial controversies on the basis of the principle of nationality and of the right to peoples to determine their own destiny and in such manner as not to infringe vital interests of the two nations as they will be defined at the moment of peace[63].

The next month, Rome hosted the Congress of oppressed nationalities, which formally brought together the Italians and the Yugoslav committee, at least in theory achieving the Italo-Slav alliance that had been hoped for by Mazzini and British South-Slav protagonists. Seton-Watson celebrated by writing in New Europe that: ‘In Rome, the spirit of Mazzini watched over the assembly.’ Torre’s agreement with Trumbić was ratified unanimously and became known as the pact of Rome. As the conference ended on the 11 April 1918, the Italian Prime Minister Orlando met up with the delegates and accepted their unanimous resolution. According to the British Ambassador in Rome, this was: ‘a sort of official recognition given to the congress.[64]’

As Austro-Hungary collapsed a week before Armistice Day, Italian troops occupied most of the Eastern Adriatic, using the Treaty of London as a justification. Italian maximalist demands, the Italian occupation and South Slav intransigence meant that the Adriatic question became the most intractable territorial issue at Versailles. President Wilson, a staunch opponent of secret diplomacy, declared the Treaty of London null and void, an act that ultimately led Italy’s Prime Minister Orlando to leave the peace conference in protest, starting the legend of mutilated victory. The Eastern Adriatic was the casus belli for intervention in the bloodiest war Italy had ever fought. Italy hoped that entering the Great War would be the culmination of the Risorgimento. Yet the Risorgimento’s revolutionary ride was corroded by the immense casualties of the war and replaced with the rottenness of reaction. Dissatisfaction with the post-war agreements meant that the social situation after the war was no better than when Carrà had painted the Metaphysical muse. Post-war irredentist ideas would claim that Italy had not gained enough territory, eventually produced the fascist dictatorship.

Tensions relating to the Italian occupation of the Eastern Adriatic coast would lead to the first fascist act in Europe according to the historian Rusinow. Taking the shooting of the Italian captain Giulli in Split in 11 July 1920, irredentist extremists in Trieste incinerated the Slovenian cultural centre in Trieste, an act saluted by Mussolini as the ‘capolavoro del fascismo triestino’. The border question was only partially resolved by the treaty of Rappalo in 1920 as Italian troops left most parts of the territory promised to them by the Treaty of London. Nevertheless, Istria, Trieste, Gorizia, Rijeka, Zadar, Lastovo and Palagruža remained in Italian hands. Ironically, the Italian irredenta had created an irredentist problem within its own country, with some 400 000 Slovenes (a third of the total population) and 100 000 Croats bitterly remaining within Italian borders continuing a problem that would erupt with even greater force in the Second World War.

For the South Slavs of the Eastern Adriatic, memories of the treaty of London, the subsequent occupation and a strong representation in the Yugoslav committee mean that union with other South Slav provinces had significant support. Like Carrà’s Metaphysical muse, the loss of territories on the Adriatic continued to haunt the conscience of the whole South Slav state. The post-war organisation, Jadranska straža (the Adriatic guard) would become one of the most numerous organisations in the new SHS state. Despite deep divisions in all fields of political life, it would be the Adriatic question that could unite south Slavs as Seton-Watson’s article in the interwar period claimed: ‘Every Yugoslav would unite to defend Dalmatia against a foreign invader[65]’. Like those on the Western Adriatic before the First World War, Slav artists like Nazor experienced the loss of the Eastern Adriatic as an amputation, musing on its loss in religious terms, promising one day to return, calm the choppy waters of the Adriatic and salvage its contested heart: ‘Hold. Wait. Do not be tired by waiting. There is a deal between you and us. Dear Istria, shorn from our parts. I bond thee, in moments like this, to all our hearts.[66]’

REFERENCES

[1] L. Monzali, The Italians of Dalmatia, Toronto 2009, p. 343

[2] Ibid, p. 323.

[3] Trieste, circolo stud. 20 Decembre, 1912, pp. 6,.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Monzali, The Italians of Dalmatia, p. 306.

[6] P. Foscari, Salviamo la Dalmazia! Il Giornale d’Italia (24 September 1914).

[7] Italy’s navy chief Admiral di Revel explains Italian claims, New York Times (14 April 1918).

[8] A. Tamaro, The Treaty of London and Italy’s national aspirations, Italian geographical society, May 1918. pp4

[9] The neutral powers, The Spectator (10 October 1914).

[10] The New Statesman (29 May 1915).

[11] Italy Daily News Reader (15 May 1915).

[12] The Near East (21 May 1915), p. 23.

[13] Lloyd George, War memoires, Boston (1934) 1 February 1915. Pp68

[14] Point 4 in the treaty of peace: “Italy shall obtain the Trentino, the Cis-Alpine Tyrol…as well as Trieste, the counties of Gorizia and of Gradisca, and the whole of Istria as far as the Quarnero, including Volosca as well as the Istrian islands of Chreso, Lussin and the smaller one of Plavnix, Unie, the Canidole, Palazzuoli, San Pietro di Nebia, Asinello, Gruice and the neighbouring isles.”

Point 5: “Italy shall also have the province of Dalmatia, according to the present administrative boundary, including Lisarica and Tribania to the north and stretching as far as the River Narenta to the south, as well as the peninsula of Sabbionello and all the islands lying to the north and west of Dalmatia itself, from Premuda, Selva, Maon, Pago and Patadura to the north, as far as Melada to the south, including Sant Andrea, Busi, Lissa, Lesina, Curzola, Cazza and Lagosta, with the neighbouring reefs, including Pelagosta.”

Communicated by Italian ambassador, March 4 1915 Italy-secret document for use of the Cabinet CAB 37/127/50-28275- British national archives, London (henceforth known as BNAL)

[15] ‘Point 14: “Great Britain undertakes to facilitate the immediate conclusion, on equitable conditions, of a loan of not less than 50 000 000, to be floated on the London market.” Ibid.

[16] Sir Edward Grey to Sir F Bertie, Sir G Buchanan, March 22 1915 CAB 37/127/50 22, 33550 – BNAL.

[17] Seton-Watson, The Adriatic Problem SEW 5/1/6 p14.

[18] Sir Edward Grey to Sir F Bertie, Sir G Buchanan, March 22 1915 CAB 37/127/50- 34053.

[19] Sir Edward Grey to Sir R Rodd, March 28 1915 CAB 37/127/50.

[20] ‘The Italian demand for Dalmatia, joined to the proposal to neutralise a large portion of the remaining Eastern Adriatic coast and the claim to the islands of the Quarnero, leaves to Serbia very restricted opportunities and conditions for her outlet to the sea…his majesties government would like to add that the three powers otherwise generally accept the Italian proposals, subject to agreement on points of detail’. Italy-secret document for use of the Cabinet, 17 March 1915 CAB 37/127/50-30951-BNAL.

[21] Sir R Rodd to Sir Edward Grey, April 2 1915 CAB 37/127/11 BNAL.

[22] Sir Edward Grey to Sir F Bertie, Sir G Buchanan, March 22 1915 CAB 37/127/50- 34053 BNAL.

[23] Sir Edward Grey to Sir G Buchanan, March 27 1915 CAB 37/127/50- 35979 BNAL.

[24] Sir Edward Grey to Sir G Buchanan, March 29 1915 CAB 37/127/50-37875 BNAL.

[25] Sir R Rodd to Sir Edward Grey, April 2 1915 CAB 37/127/11 BNAL.

[26] Communicated by Russian ambassador, 17 March 1915 Italy-secret document for use of the Cabinet CAB 37/127/50-31544, BNAL.

[27] Sir G Buchanan to Sir Edward Grey, March 27 1915 Ibid.

[28] 2 April 1915 CAB 37/127/11 BNAL.

[29] Monzalli, The Italians of Dalmatia, p. 318.

[30] Ibid.

[31] ‘The safeguard of the west…Venice the eldest child of liberty’ Wordsworth, On the extinction of the Venetian republic, 1802.

[32] What Italy brings to the Allies The Spectator (29 May 1915).

[33] R. Seton-Watson, Spirit of the Serb, lecture given at Kings College London, March 1915.

[34] In a polemic with the Italian Cambridge professor Piccoli, Seton-Watson refuted claims that he was anti-Italian, asserting that: ‘I was brought up to love Italy and her language, to admire the heroes of the Risorgimento, and sympathy with their ideals have been with me an additional reason for sympathising with the Southern Slavs in their national resurrection’ Pall Mall Gazette (16 December 1916).

[35] D. Djokic, Yugoslavism-histories of a failed idea, London 2003, p. 31.

[36] Seton-Watson, Italy and the South Slavs. Letter to the Times (22 April 1915).

[37] Ibid.

[38] Seton-Watson, Italy and the South Slavs (22 April 1915).

[39] Seton-Watson, Italy and the South Slavs (22 April 1915).

[40] This idea is explored in: Dominique Kirchner Reill, Nationalists who feared the nation. Adriatic Multi-Nationalism in Habsburg Dalmatia, Trieste, and Venice, Stanford 2012.

[41] Seton-Watson The Adriatic Problem SEW 5/1/6 p. 12.

[42] Seton-Watson, Italy and Dalmatia (29 May 1915).

[43] Seton-Watson, The Adriatic Problem SEW 5/1/6 p. 27.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Hugh and Christopher Seton-Watson, The making of new Europe, London 1981, p. 106.

[46] Les italiens et les yougoslaves dans la pensée de Giuseppe Mazzini, Le bulletin yougoslave (10 October 1915).

[47] The Times (12 May 1915).

[48] Telegram from Supilo to the British Prime minister FO 371 2257, BNAL.

[49] Italy’s other shore, Sara Lady’s Pictorial 28 August 1915.

[50] Reported in Near East on the 2 July 1915 SEW 7/2.

[51] The Near East Ernest H.R Collings, 21 May 1915.

[52] I. Mestrović, Uspomene na ljude i događaje, Zagreb, Matica Hrvatska, 1969 p. 45.

[53] Seton-Watson archive SSEES SEW 3/1/1.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Mestrović, Uspomene na ljude i događaje, p. 49.

[56] Telegram by Sir Buchanan from Petrograd 7 May 1915 FO 371 55816, BNAL.

[57] Légation royale de Serbie Aide-mémoire 21 May 1915 FO 371 63945, BNAL.

[58] Mestrović, Uspomene na ljude i događaje, p. 58.

[59] Seton-Watson, Yugoslavia in the making- New Europe Seton Watson Arhive 2/1/3 p. 17.

[60] Mestrović, Uspomene na ljude i događaje, p. 89.

[61] Seton-Watson, Yugoslavia in the making- New Europe, Seton Watson Archive 2/1/3 p. 23.

[62] Seton-Watson, The making of new Europe, p. 243.

[63] Ibid, p. 250.

[64] Seton-Watson, The making of new Europe, p. 266.

[65] R. Seton-Waton, Jugoslavia and the Croat Problem, in: The Slavonic and East European Review, vol. 16/no. 46 (1937), p. 10.

[66]V. Nazor, Selected works published in: Jurina and Franina Annual, Pula 1954.pp 34

BIBLIOGRAPHY

PRIMARY SOURCES

- National Archives, Public records office London

- Italian diplomatic documents 1914-15

- Seton Watson Archives London school of Slavonic studies.

- Seton-Watson, R Spirit of the Serb Lecture given at Kings College London, March 1915

- Seton-Watson The Southern Slav question and the Hapsburg monarchy, Constant Ltd (1911)

- Lloyd George War memoires, (1938)

SECONDARY SOURCES

- Monzalli, L- The Italians of Dalmatia University of Toronto Press (2009)

- Hugh and Christopher Seton-Watson The making of new Europe Methuen (1981)

- Mestrović, I Uspomene na ljude I događaje Matica Hrvatska (1969)

- Lloyd George, War memoires, (1938)

- Djokic, D Yugoslavism-histories of a failed idea Hurst (2003)

NEWSPAPERS

- Il Giornale d’Italia

- The Times

- The New York Times

- The Times

- Lady’s pictorial

- The nation

- The near East

- Corriera della Sera

- The Guardian

- The Spectator

- Le bulletin yougoslave

- The Fortnightly Review

JOURNALS

- Britain and Italian intervention 1914-15 (1969) J Lowe The historical journal- XII Vol 3

- Italy and the outbreak of the First World War (1954) Pryce, R Cambridge historical journal Vol 11, no2

- Jugoslavia and the Croat Problem (Jul., 1937) Seton-Waton, R The Slavonic and East European Review,

- Italy and the outbreak of the First World War (1954) Pryce, R Cambridge historical journal Vol 11, no2

- The scramble for the Adriatic (2013) Klabjan, B Austrian History Journal Vol 2

INTERNET

www.14-18.it